India-Pakistan on the Brink: Forecasts for what happens next

How a 76-year fight over water rights and national pride risks nuclear conflict

About the author: Peter Wildeford is a top forecaster, ranked top 1% every year since 2022. Here, he shares the news and analysis that informs his forecasts.

On April 22nd, a terrorist attack in Indian-administered Kashmir resulted in the deaths of 27 people, mostly Hindu tourists. India has blamed Pakistan for supporting the attack, which Pakistan denies.

In response, India launched military strikes against Pakistan, attacking what India claims is “terrorist infrastructure” at nine sites in Pakistan and Pakistan-administered Kashmir. Pakistan has vowed to retaliate.

The situation is rapidly evolving, with both sides exchanging fire across the Line of Control that divides India-controlled and Pakistan-controlled Kashmir. This represents the worst escalation of tensions between the nuclear neighbors in over two decades.

Most notably, this is happening under the background of both Pakistan and India being nuclear-armed nations.

Here are my forecasts for what happens next:

Will either India or Pakistan detonate a nuclear weapon in the other's territory by the end of 2025? 1%

The Indus Waters Treaty is a key treaty between Pakistan and India that has survived multiple prior wars and is existential for Pakistan getting the water it needs for irrigation and agriculture. India is up-river from Pakistan and can control Pakistan’s water supply. If India were to restrict water to Pakistan, it could potentially approach Pakistan's “economic strangulation” threshold for nuclear use. This creates a uniquely dangerous escalation pathway separate from conventional military conflict.

However, both countries comprehend the devastating impacts of nuclear exchange, providing strong incentives for maintaining escalation control despite heated rhetoric. And despite diplomatic breakdowns, military-to-military communications channels remain operational, providing a critical de-escalation mechanism.

Another India military strike on Pakistan by the end of Friday?1 40%

We’re already in the response cycle, with Pakistan retaliating to India’s attacks with artillery exchanges and claiming to have destroyed Indian military aircraft. If Pakistan's forthcoming response causes significant casualties, it could provoke India to attack again.

However, historical response pattern shows that India typically conducts a single major retaliatory operation following terrorist incidents rather than multiple sequential strikes.

And India’s attack was substantial in scope (targeting nine locations) and described by Indian officials as “focused, measured, and non-escalatory,” suggesting it was designed as a complete response rather than the first phase of a larger campaign.

Will India invade Pakistan by the end of June?2 8%

Both nations have suspended foundational treaties in a way that hasn’t happened before, suggesting a new low water mark for diplomatic guardrails. This suggests it is possible the conflict could go in directions not seen in many decades.

India has also begun civil defense drills across seven states — a measure not seen since the 1971 war, suggesting serious military preparations.

Spring/summer is historically favorable for military operations in the region, with prior conflicts beginning in April-May when mountain passes become accessible.

However, Pakistan’s nuclear deterrence remains a huge barrier to India. Additionally, China-Pakistan military cooperation forces India to consider the risk of a two-front war. On top of that, there would be significant international diplomatic costs to India launching a full-scale invasion. It’s not clear what India would gain from an invasion and it seems like they have a lot to lose.

Will conflict between India and Pakistan result in 100 deaths by the end of June?3 40%

As of the time of writing, the current death toll already at ~38.4 This means 62 more deaths would be needed over the next two months, requiring a notable escalation in the current conflict.

Minor skirmishes typically result in 5-20 casualties per incident, while moderate military operations (which this conflict has already entered) usually result in 100-500 casualties.

Pakistan has explicitly vowed to retaliate for India's May 7 strikes — despite some minor attacks from Pakistan, their full response is still expected to be forthcoming as of the time of writing. If Pakistan's response involves substantial airstrikes or artillery across multiple locations (rather than just symbolic strikes), casualties will likely surge toward or beyond the 100-death threshold.

But there are still many off-ramps for de-escalation and de-escalation has been the norm in prior conflicts. Prior recent India-Pakistan skirmishes, including in 2019, have not yielded 100 deaths in such a two-month timeframe — the most recent time this happened was in 1999.

Additionally, Pakistan's fragile $350 billion economy, recently emerged from crisis and operating under a $7 billion IMF program, gives it powerful incentives to avoid prolonged conflict that would devastate its economy further.

The Dispute over Kashmir

Why is this happening?

The current India-Pakistan crisis represents the most serious confrontation between the nuclear-armed neighbors since 2019. Tensions have escalated beyond typical response patterns seen in previous conflicts, especially with the unprecedented suspension of the Indus Water Treaty that had survived all the previous wars.

The key to the current India-Pakistan conflict is conflict over the region of Kashmir. Kashmir has split control between India and Pakistan, but is claimed in entirety by both nations — a classic border dispute. However, there’s more on the line than just national pride. The most important reason for dispute over Kashmir is water security.

The Indus River Basin, which is critical for the livelihood of nearly three-fourths of Pakistan's population, flows through Indian-controlled territory in Kashmir. Control over the Indus River's source and its tributaries is of immense economic and strategic importance, as it's vital for Pakistan's agricultural sector. This is why Kashmir is so important to Pakistan. This resource dependency creates a fundamental security concern for Pakistan.

For India, the region also provides additional buffer between China (as well as Pakistan) and critical mountainous regions for national defense. And furthermore, the conflict has become interwoven with national identity and domestic politics.

But how did this dispute come about? Why is Kashmir disputed in a way that other parts of India and Pakistan are not?

The British Partition

The answer, like most border conflicts, is that it is the fault of the British.

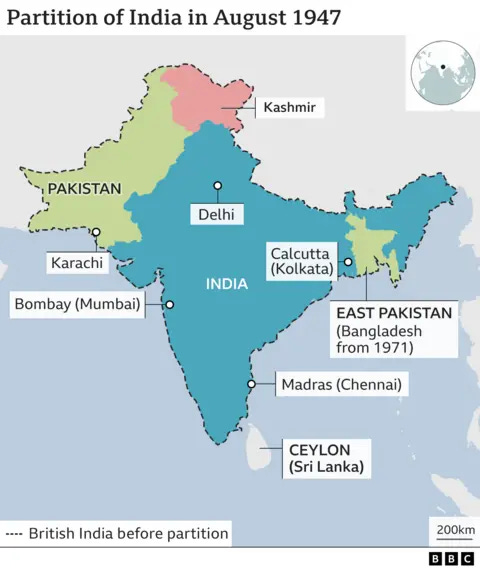

Before 1947, the entire Indian subcontinent was under British colonial rule as “British India.” British India included not just modern-day India, but also modern-day Pakistan, Bangladesh, Burma (until 1937), and some parts of other nations. Additionally, there were also princely states that, during British Rule, were still semi-autonomous kingdoms with their own monarchs (called Maharajas, Nawabs, etc.). Kashmir was one of these princely states.

After WWII, Britain was financially exhausted and faced pressure to decolonize, and Indian independence activism had intensified, along with religious tensions. Britain decided on a hasty withdrawal, accelerating the timeline for independence.

The Partition of 1947 was specifically designed to create two fully independent countries — India and Pakistan — as part of the end of British colonial rule in the area. Pakistan in particular was two non-contiguous regions, West Pakistan (modern day Pakistan) and East Pakistan (modern day Bangladesh). Kashmir was included as part of this partition, but was neither in the Indian nor Pakistan regions.

The partition was made based on religion. Kashmir was majority Muslim, making it a natural fit for Pakistani control. However, being a princely state and not part of British direct rule, Kashmir was given a choice of whether to fall under Pakistan or India. But along with its predominately Muslim population, Kashmir had a Hindu ruler, Maharaja Hari Singh. Kashmir was also geographically split, being close to both India and Pakistan. It could go either way. But instead Kashmir chose neither — Kashmir wanted to join neither India nor Pakistan but instead wanted full independence.

However, this wasn’t an option. In October 1947, tribal militias from Pakistan's border regions invaded Kashmir. These militias were unofficially supported by Pakistan to force the issue of control and prevent Kashmir from potentially joining India. But this was a self-fulfilling prophecy on behalf of Pakistan — Singh faced imminent defeat and desperate for military assistance, Singh agreed for Kashmir to join India in order to get military aid. Indian troops then pushed back the invading forces.

This triggered the First Kashmir War. Pakistan officially joined the fighting after initially using only tribal militias. The war lasted until for two years, ending with a UN-mediated ceasefire. The ceasefire line — later called the Line of Control — divided Kashmir between Indian and Pakistani control, with India having the majority of the Kashmir territory. This line was decided based on where military control was at the time of the ceasefire, essentially freezing the conflict where it stood rather than through any principled territorial division. Additionally, Article 370 was adopted into the Indian Constitution, which granted special autonomous status to the Indian-controlled part of Kashmir.

Moreover, recognizing the fundamental issue of water security, The Indus Water Treaty was agreed between India and Pakistan, to use the water available in the Indus River and its tributaries. It was signed in 1960. The treaty is vital for Pakistan, as it's heavily dependent on water from this river system for its hydropower and irrigation needs. However, India has leverage here as the upstream controller of the river, with the river flowing first into India-controlled Kashmir before flowing into Pakistan-controlled Kashmir and then Pakistan itself.

The conflict becomes nuclearized

India's nuclear program began in March 1944, out of a need for strategic deterrence against China, especially after India's defeat in the 1962 Sino-Indian border war. India built its first research reactor in 1956 and first plutonium reprocessing plant by 1964. India currently possesses approximately 164 nuclear warheads and maintains land-based, sea-based, and air-launch nuclear capabilities. However, India has declared a “no-first-use” policy, meaning it has vowed never to use nuclear weapons first in a conflict.

Pakistan's nuclear program was a direct response to India's development of nuclear weapons. Today, Pakistan has approximately 170 warheads. Unlike India, Pakistan has not declared a “no-first-use” policy, and instead emphasizes smaller battlefield or “tactical” nuclear weapons as a counter to India's larger and superior conventional forces.

Both sides having nuclear weapons also provides for a classic stability-instability paradox, where the presence of nuclear weapons can deter large-scale war but paradoxically increase the likelihood of lower-intensity conflicts and proxy wars as larger-scale conflict is less likely to be a deterrence. While limited military exchanges remain the most likely scenario, the risk of unintended escalation is higher than in previous crises due to weaker crisis management mechanisms, more clearly aligned external powers, and domestic political pressures on both sides.

Temporary peace and terrorist attacks

After the 1972 Simla Agreement and throughout each country’s nuclear developments, Kashmir actually entered a period of relative stability. But in 1987 Kashmir state elections within India were widely perceived as rigged, with ballot boxes being pre-stamped in favor of National Conference candidates, polling agents being arrested and beaten, and vote counting being manipulated. This created deep resentment within Indian-controlled Kashmir and marked the beginning of an organized anti-India insurgency.

Many Kashmiris, particularly young people, appear highly critical of Indian presence. But when surveyed about conflict resolution, only about 64% of Kashmiri students thought requesting help from Pakistan would be effective — significantly lower than other proposed solutions. This suggests limited faith in Pakistan as an ally. When asked about paths to peace, Kashmiri students overwhelmingly (91%) supported a plebiscite allowing them to determine their own future. This reflects a desire for self-determination rather than automatic alignment with either country.

Several significant terrorist attacks, including the 2008 Mumbai attacks, periodically derailed diplomatic progress and Kashmir saw cycles of civilian protests, notably in 2008, 2010, and 2016, with growing youth participation. 2019 began with the Pulwama Attack in February, a suicide bombing in Indian-controlled Kashmir, where a vehicle packed with explosives targeted a convoy of Indian paramilitary forces, killing 40 Central Reserve Police Force personnel, the deadliest attack in Kashmir in three decades.

Indian response and suspension of Kashmir

In response to the Pulwama Attack, India launched what it called “non-military preemptive action” — airstrikes targeting an alleged terrorist training camp in Balakot, Pakistan. This marked the first time since the 1971 war that India had conducted airstrikes on undisputed Pakistani territory (rather than in the contested Kashmir region). This sounds remarkably similar to the conflict today.

The next day, Pakistan retaliated with its own airstrikes in Indian-administered Kashmir. In the ensuing aerial battle Pakistan shot down an Indian MiG-21 and captured its pilot. The crisis threatened to escalate further but was defused when Pakistan returned the captured Indian pilot two days later.

But the most transformative event for Kashmir came in 2019 August, when India's government unilaterally revoked Article 370 of the Indian Constitution, which had granted special autonomous status to Kashmir since 1949. Simultaneously, India imposed an indefinite security lockdown in Kashmir, and detained thousands of Kashmiris, including political leaders. This move fundamentally changed Kashmir's relationship with India, eliminating the semi-autonomous status it had maintained since accession in 1947 and opening the region to settlement by non-Kashmiris.

These events of 2019 collectively represented the most significant reshaping of the Kashmir situation in decades and created the conditions for the ongoing tensions that have continued to the present day, including the recent escalation following the 2025 Pahalgam attack.

The current flashpoint

On April 22, 2025, armed militants attacked tourists in Baisaran Valley near Pahalgam, killing 26 people (25 Indian tourists and one local Muslim) and injuring over a dozen others. The attack, which targeted Hindu male tourists, represents the deadliest attack on civilians in Kashmir since the early 2000s.

India blames Pakistan based on Indian authorities linked two of the three terrorist suspects allegedly involved in the attack as Pakistani nationals and the historical pattern of Pakistan's alleged support for cross-border terrorism. Pakistan denies these claims.

As a result of the Pahalgam attack, the Simla Agreement formalizing the Line of Control was suspended and the Indus Waters Treaty, which had survived three prior wars, was revoked. Both Pakistan and India have closed their borders with each other and expelled each other’s diplomats, and increased military mobilization.

Additionally, over May 6-7, India launched a missile strike targeting alleged terrorist camps in Pakistan.

Today’s geopolitical and military situation

India and Pakistan’s military situation is determined by India having overwhelming conventional military force but Pakistan having nuclear parity. India maintains a significant conventional military advantage over Pakistan across all domains, with India's 1.45M active military personnel dwarf Pakistan's ~650K, India having a 150% advantage in both tanks and aircraft, and an 8:1 advantage in military spending.

However, this conventional disparity is offset by Pakistan's nuclear arsenal. As of 2024, India possessed approximately 172 nuclear warheads compared to Pakistan's 170.

The Trump administration (2025) has adopted a relatively hands-off approach to the current crisis. Despite this, the US has shown a clear tilt toward India, viewing it as a crucial counterweight to China in the Indo-Pacific region. At the same time, China remains Pakistan's “all-weather friend” and primary economic lifeline through the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), expected to reach $65 billion in investments by 2025.

Previous India-Pakistan crises provide insight into potential escalation and de-escalation patterns. Thus based on precedent, the most likely near-term scenario involves a limited exchange of fire followed by international pressure leading to de-escalation.

However, the current crisis differs from these precedents with unprecedented treaty suspensions including the Indus Waters Treaty, reduced US diplomatic engagement in South Asia, greater Chinese investment in Pakistan, and higher risk tolerance demonstrated in recent years. Several key de-escalation mechanisms that proved effective in previous crises, such as third-party mediation and back-channel diplomacy, appear weaker in the current environment.

There’s also some additional domestic sentiment pushing closer to war. In India, Prime Minister Narendra Modi began his third term in June 2024 following the general election. However, his BJP won only 240 seats (down from 303 in 2019), falling short of a majority and requiring coalition partners for the first time since 2014. This reduced parliamentary majority potentially increases pressure on Modi to demonstrate strength in external affairs.

Similar dynamics are present on the Pakistani side as well. Anti-Pakistan protests have erupted across Indian cities following the Pahalgam attack, while demonstrations in Pakistan show support for the government's stance against India's allegations.

What to watch

The coming weeks will prove critical in determining whether they can step back from the brink or stumble into a conflict neither truly desires.

If Pakistan's response causes significant Indian civilian casualties or damages critical infrastructure, India would be much more likely to conduct additional strikes. Prolonged artillery duels across the Line of Control without clear de-escalation would indicate an unstable situation where additional strikes become more likely. And any further reduction in water flow through the Indus Waters system by India would represent a significant escalation from Pakistan's perspective, potentially triggering more dramatic responses.

As this nuclear-armed standoff intensifies, the stakes for regional and global security could not be higher. Even a small nuclear exchange between India and Pakistan could kill 20 million people in a week, and if a nuclear winter is triggered, nearly two billion people in the developing world would be at risk from starvation.

The current conflict represents not just the latest chapter in a historical dispute, but potentially the most dangerous escalation in decades between two nations that together account for nearly one-fifth of humanity.

This is defined with reference to this Polymarket question.

This is defined with reference to this Polymarket question.

This is defined with reference to this Metaculus question.

From Operation Sindoor strikes (26 Pakistani civilians) and cross-border shelling (12 Indian civilians).

Exceptionally well researched and written. You might consider approaching a major foreign policy organization about reprinting this.