AI is probably not a bubble

AI companies have revenue, demand, and paths to immense value

About the author: Peter Wildeford is a top forecaster, ranked top 1% every year since 2022.

Is AI a bubble? Goldman Sachs CEO David Solomon, Ray Dalio, Sequoia’s David Cahn, the International Monetary Fund, and the Bank of England are all saying so. Former Intel CEO Pat Gelsinger put it bluntly: “Are we in an AI bubble? Of course. Of course we are.” Altman repeated the word “bubble” three times in 15 seconds at a dinner with reporters.

But the twist is that most of these people are saying “yes, it’s a bubble” while simultaneously announcing they’re spending hundreds of billions more. Zuckerberg says a collapse is “definitely a possibility” but insists underinvesting is worse. OpenAI’s Sam Altman warns investors will get “very burnt” while still planning $850 billion in data center buildouts. Jeff Bezos says AI is in an industrial bubble while Amazon spends $100B/yr in AI R&D.

How do we make sense of this?

OpenAI’s meteoric rise

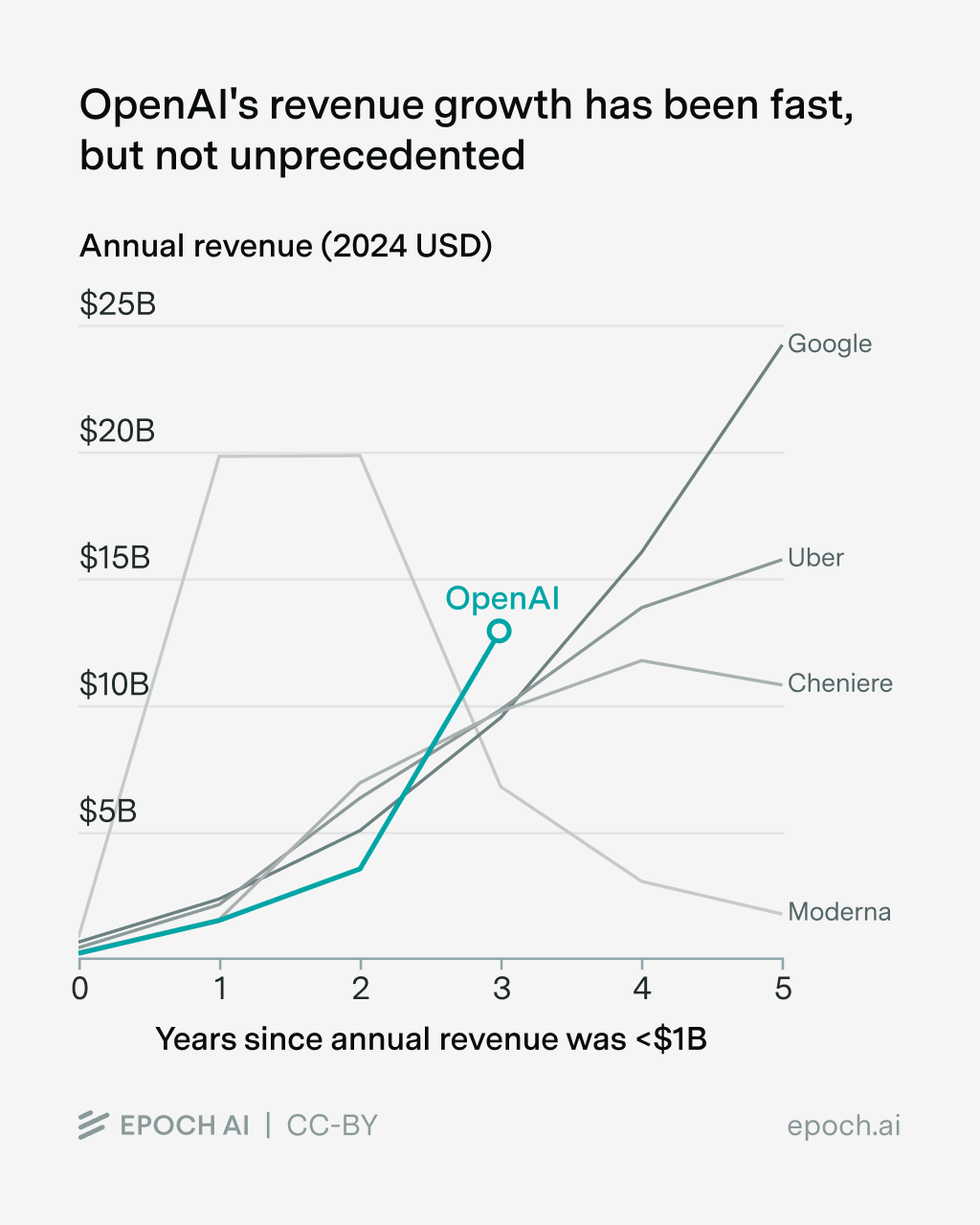

Back in March 2023, OpenAI reported $200M in annualized revenue.1 Incredibly, this annualized revenue passed $1B just five months later, at the end of August 2023. It then continued upward quickly — passing $2B in December 2023, $3B in June 2024, $5B in December 2024, and $10B in June 2025, and now is at $13B as of August 2025.

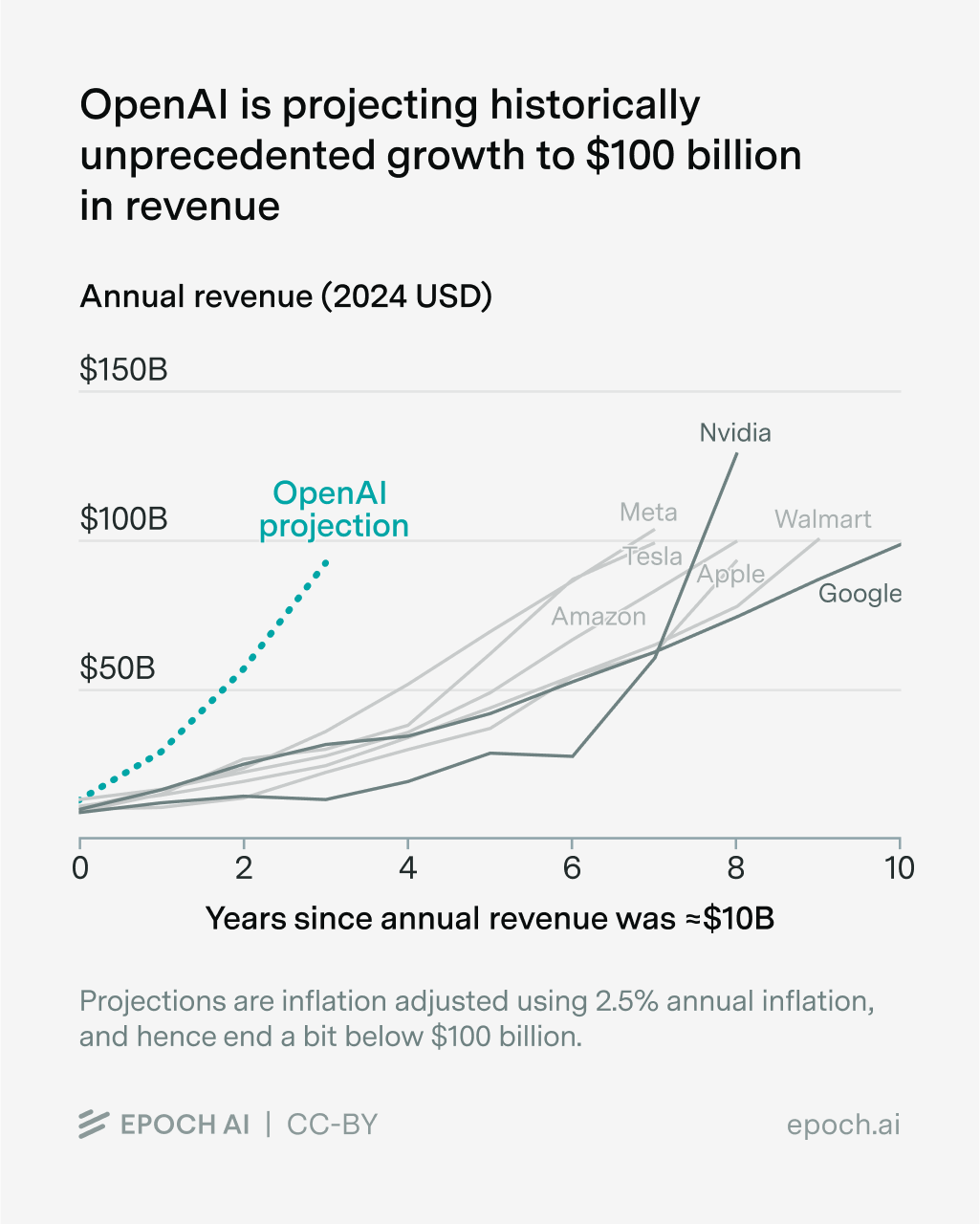

This massive revenue growth has been fast, but is not unprecedented — EpochAI found it to be on a similar trajectory to Google in 2003-2006, Uber in 2015-2020, and Cheniere (a US liquified natural gas company) in 2016-2020:

This massive revenue growth has helped give OpenAI a $500B valuation, making OpenAI the most valuable private company, newly ahead of the $400B SpaceX. If OpenAI were a public company on the stock market with the same valuation, it would be the 18th largest, edging out Exxon Mobil and Netflix but not quite surpassing Mastercard.2

Big revenue meets even bigger spending

This is important because OpenAI has a lot of bills to pay for AI infrastructure, especially cloud computing, chips, and data centers… OpenAI has committed to a $300B cloud deal with Oracle that begins in 2027 and runs for 5 years, a $100B investment from NVIDIA that will be used entirely to buy NVIDIA chips, a $22.4B cloud deal with CoreWeave3, a “tens of billions” deal with Broadcom for custom AI chips, a $90-100B deal with AMD for chips …and OpenAI is still in on the $500B+ Stargate deal, with plenty of data centers to build too.

And OpenAI is just getting started. Bloomberg quotes OpenAI CEO Sam Altman as saying:

You should expect OpenAI to spend trillions of dollars on infrastructure in the not very distant future. And you should expect a bunch of economists to say, ‘This is so crazy, it’s so reckless, and whatever […] And we’ll just be like, ‘You know what? Let us do our thing. […]

I suspect we can design a very interesting new kind of financial instrument for finance and compute that the world has not yet figured it out.

As a result of all these investments, OpenAI is not currently close to profitable.

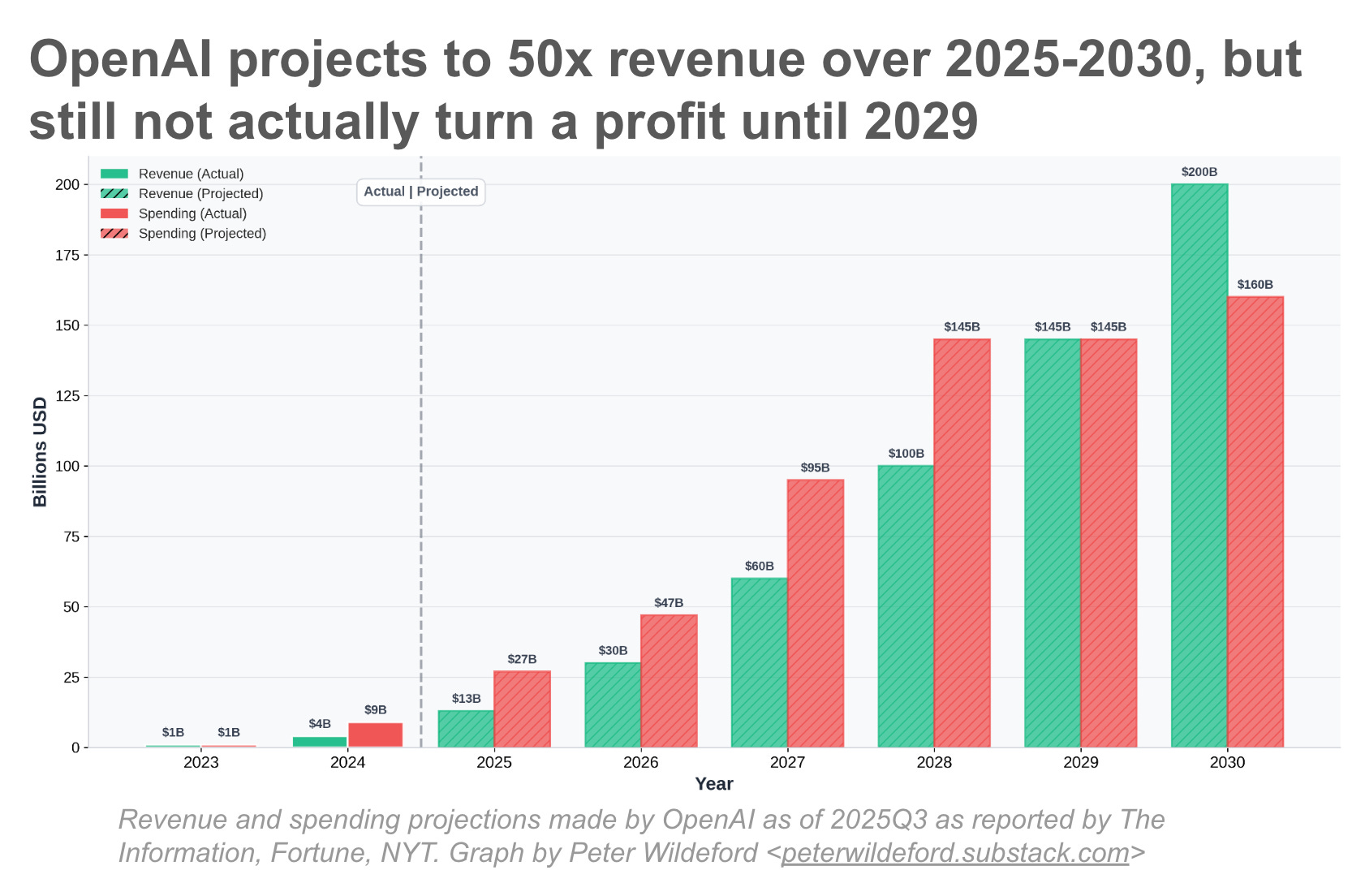

OpenAI lost $5 billion in 2024 on $9 billion in total spending. The Information reports that this will only increase — OpenAI is projected to lose $14B in 2025, $17B in 2026, $35B in 2027, and $45B in 2028… this makes for a stunning situation where OpenAI is projecting unprecedented revenue growth over the next five years but still not breaking a profit until 2030:

There are three factors that are unprecedented about OpenAI’s spending — each merit deeper inspection.

Firstly, OpenAI is racking up record losses on its infrastructure buildout. WeWork burned through $22B total before bankruptcy, but never came close to OpenAI’s projected $116B. Uber also famously had a “burn money fast to gain market share and then later figure out how to be profitable” strategy but their cumulative losses peaked around $23B. OpenAI is just operating at a whole different level of scale.

Secondly, OpenAI’s projected revenue growth is itself unprecedented. EpochAI finds that while OpenAI’s revenue has tripled annually between 2023 and 2025, only seven US companies have grown from $10 billion to $100 billion within a decade, and none in under seven years — while OpenAI plans to do that in three.

EpochAI visualizes OpenAI’s projected revenue growth, going from ~$10B in 2025 (year 0 on the graph for OpenAI) to ~$100B by 2028 (year 3 on the graph). Compared to other companies, this projection is very fast growth!

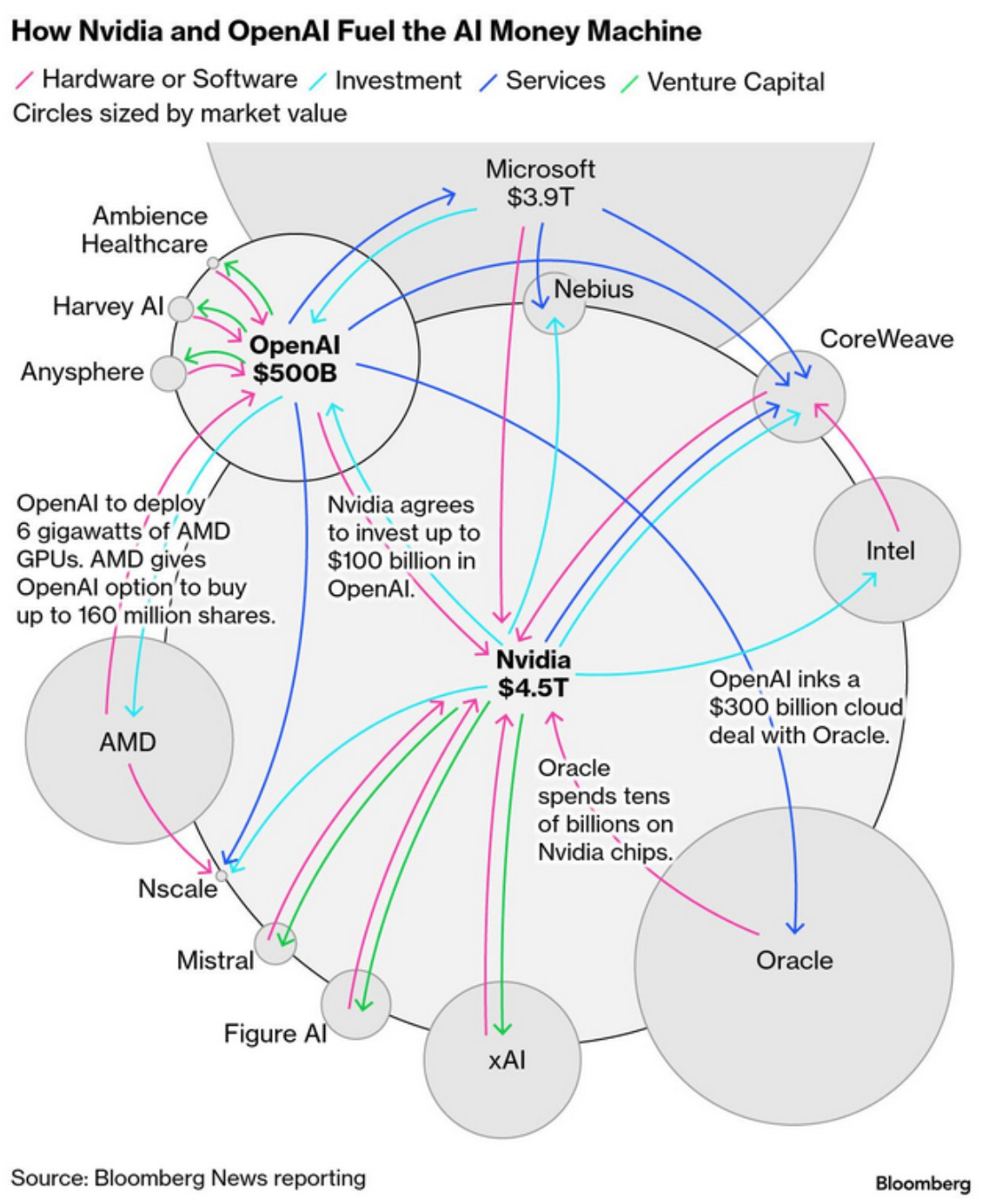

Thirdly, the deeply entangled financing. I covered earlier this month one of these circles, where NVIDIA invests in OpenAI, which spends the money on NVIDIA chips and Oracle compute, while Oracle buys more NVIDIA hardware to serve OpenAI. This meant the NVIDIA capital goes in a big circle from NVIDIA to OpenAI to Oracle back to NVIDIA.

Since then, there’s been similar deals with OpenAI and AMD and the circle has gotten bigger. Bloomberg did a good job of diagramming it:

So how does this all add up to a potential bubble? Due to all this circular investment, OpenAI’s future cash flow is now a sizable part of the valuations of all of Nvidia, Microsoft, AMD, and Broadcom. These companies are priced in large part assuming OpenAI’s success will continue to drive sustained demand. And these companies are a large part of the stock market.

This is combined with the risk that OpenAI misses their revenue goals, since OpenAI’s projection is unprecedented and untested. And if OpenAI misses their revenue goals, there could be a correction in the stock market. And because AI spending is now a large driver of broader US economic growth, this correction could generate a real recession. In short, a bubble popping.

Dot com and the art of the bubble

The most familiar bubble is the dot-com bubble in the late 1990s when there was a lot of exuberance about companies first selling on the internet. Many have attempted to draw a comparison to AI and the dot-com bubble. Pets.com failed spending $300 million in 268 days to sell each product at a loss. Webvan raised $800 million for online grocery delivery before operating a single profitable market.

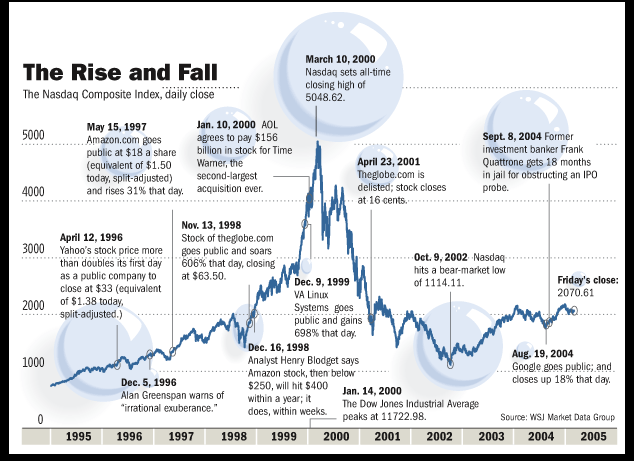

The dot com boom powered 600% growth in the stock market between 1995 and 2000. But then interest rate increases killed the cheap-money fuel that was powering investment in these companies. This exposed the broader problems in the stock market. Everything crashed back down to 1995-levels, with a 78% drop.

The dot-com bubble shows that business models can be correct in principle but economically unsustainable at current technology maturity and cost structures. But a key difference between dot-com and AI is that the dot-com bubble was about companies who had bad unit economics — “we lose money on every sale, but make it up in volume.”

However, unlike dot-com companies, the AI companies have reasonable unit economics absent large investments in infrastructure and do have paths to revenue. OpenAI is demonstrating actual revenue growth and product-market fit that Pets.com and Webvan never had. The question isn’t whether customers will pay for AI capabilities — they demonstrably are — but whether revenue growth can match required infrastructure investment. If AI is a bubble and it pops, it’s likely due to different fundamentals than the dot-com bust.

And notably, the internet ended up ultimately transformative technology and many 90s internet companies did succeed, such as Amazon, Microsoft, and Apple. Even Pets.com and Webvan were eventually replaced by the successful Chewy and Instacart.

Infrastructure bubbles — or “What do British railways and AI have in common?”

Instead, if the AI bubble is a bubble, it’s more likely an infrastructure bubble.

Consider Britain’s Railway Mania of the 1840s. The Liverpool and Manchester Railway, opened in 1830, generated 10%+ annual returns and demonstrated railways could dramatically reduce transportation costs. This success triggered an explosive investment. Between 1844 and 1847, Parliament authorized over 8,000 miles of new rail construction.

Multiple companies laid parallel routes, each assuming they would capture market share. But a lot of the new routes were not profitable. When the crash came in 1847, thousands of investors lost fortunes. Yet the infrastructure remained valuable, powering Britain’s industrialization through the late 19th century. The technology thesis proved correct; the financial structure was catastrophic.

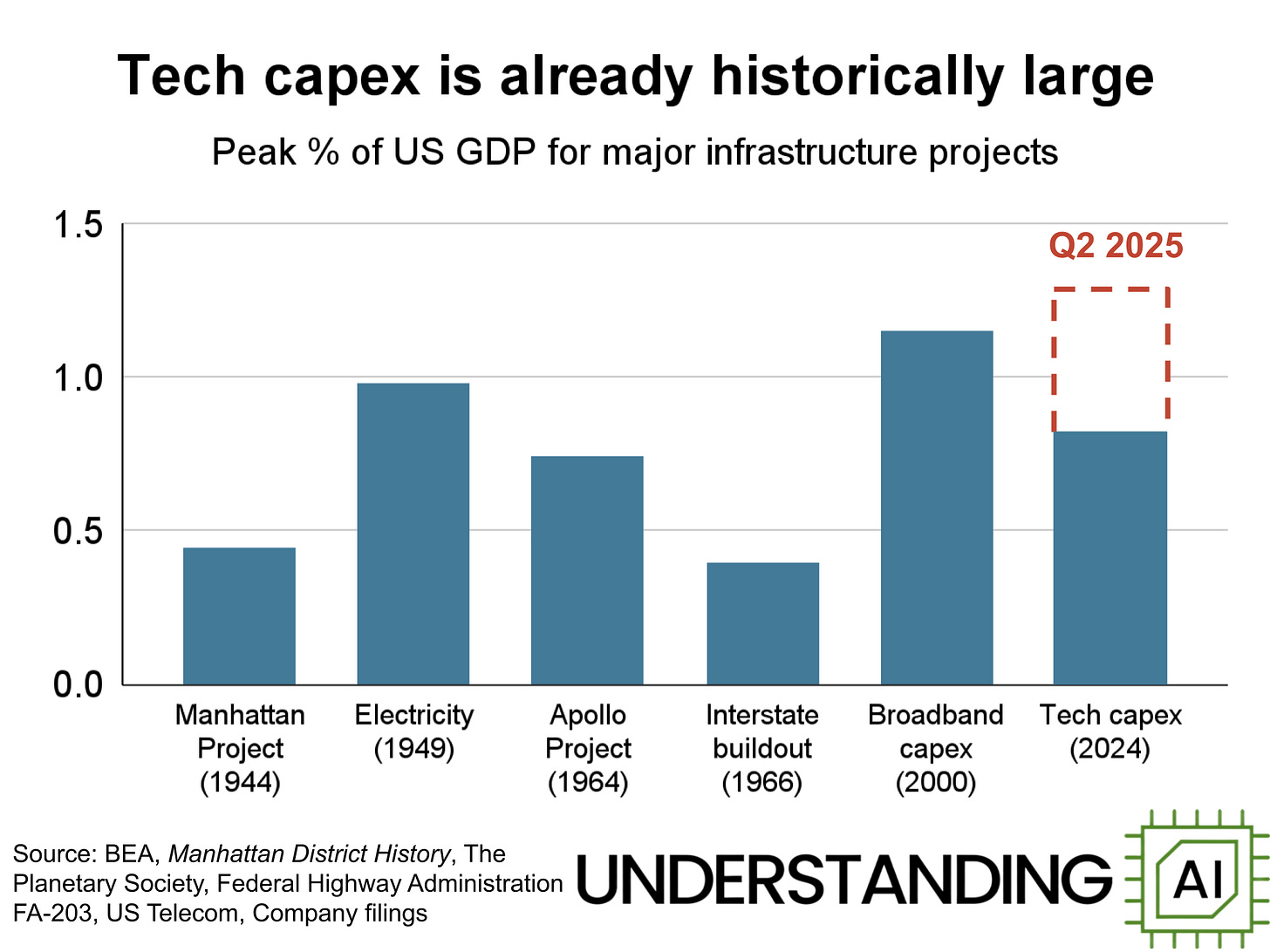

The telecommunications crash of 1997-2002 followed a similar pattern. The thesis was sound — explosive internet growth would require massive bandwidth capacity. Companies laid millions of miles of fiber optic cable, with industry capital expenditures reaching $600B from 1997 to 2001. But the simultaneous construction by competitors created catastrophic oversupply and a significant portion of the fiber was installed but unused. Though the fiber ultimately did end up seeing use over the next two decades, this was far too late for original investors.

Infrastructure bubbles follow a recognizable arc. A genuinely transformational technology emerges and early deployments generate spectacular returns, validating the concept. Capital floods in at scale as investors extrapolate from initial successes. Multiple competitors simultaneously build capacity, each assuming they’ll capture significant market share. When aggregate capacity vastly exceeds near-term demand, the surplus can’t generate the revenue needed to pay for itself, and the financial structures collapse. Companies fail, investors lose fortunes, and infrastructure sits idle. The technology often still ultimately proves transformative, just too late for original investors.

It’s not as weird as it looks

However, unlike railway track sitting idle for years, AI data centers are being utilized immediately upon completion. OpenAI’s Abilene facility began running workloads as soon as capacity came online. Lead times for advanced GPUs stretch months, and energy availability limits deployment more than capital. The constraint is currently supply, not demand — which is why companies are aiming to build as much as possible.

The telecom parallel has more validity. We do have multiple companies building competing infrastructure and we do have multiple AI companies training competing models. This creates risk of redundant capacity. However, AI infrastructure shows more flexibility than fiber optic cable. GPUs can run various workloads, data centers can host different services, and cloud capacity potentially retains value even if AI-specific demand disappoints.

Additionally, NVIDIA and OpenAI’s circular financing is unprecedented in scale, but not fundamentally unsound. It’s similar to how a car company might give you a loan to buy their car — in this case, the money is still circular, but provided you do pay back the loan, everything works just fine. Except in this case, it’s NVIDIA renting chips on a loan to OpenAI rather than a car company renting a car on a loan.

Also the accusations of circular financing apply primarily to OpenAI’s situation, which is a minority of the broader investment wave. Microsoft, Meta, Google, and Amazon have immense pre-existing cash flows to pay for their infrastructure buildout without taking on debt. NVIDIA is only doing this for their customers who don’t have the immediate cash to buy the chips. And NVIDIA also has significant revenue of their own to be able to absorb big hits from bets that don’t pan out.

The bigger issue instead is what happens if AI doesn’t pan out. This, rather than vendor financing, is what would drive a stock market correction or even a recession. NVIDIA’s $5T market cap assumes sustained AI infrastructure spending. Microsoft’s $4T market cap includes a large premium for AI-driven productivity gains. If OpenAI’s revenue trajectory flattens and infrastructure spending is cut because AI-driven productivity doesn’t pan out, this will cause all these expectations repriced downward. So the real question is whether AI capabilities will be there on the timelines needed to generate revenue.

The fundamentals of the technology are different

Companies like Google and Facebook have already demonstrated that a product that is modestly useful to billions of people can be sufficient to generate hundreds of billions of dollars in annual revenue. OpenAI has a similar level of user base with over one billion free users, and it seems plausible these users could be monetized in some way. This is the basic Facebookization of AI that seems underway already. AI is not like blockchain, crypto, NFTs, or the metaverse — there is already real value being delivered.

But this revenue and other investment can just be a prelude to the true bull case of AI — AGI that automates the entire economy. If AGI were made, the winner theoretically gets not just some billions in annual revenue, but the entire economy! And along the way to automating the entire economy, maybe AI automate smaller parts of the economy that still deliver economic returns?

Imagine if the way British Railway Mania worked was not just that additional tracks could produce additional economic value, but that some amount of track (actual amount unknown) would somehow allow the rail company to monetize a cure for cancer, successfully compete with basically every other company in the economy, and potentially even take over the entire world?

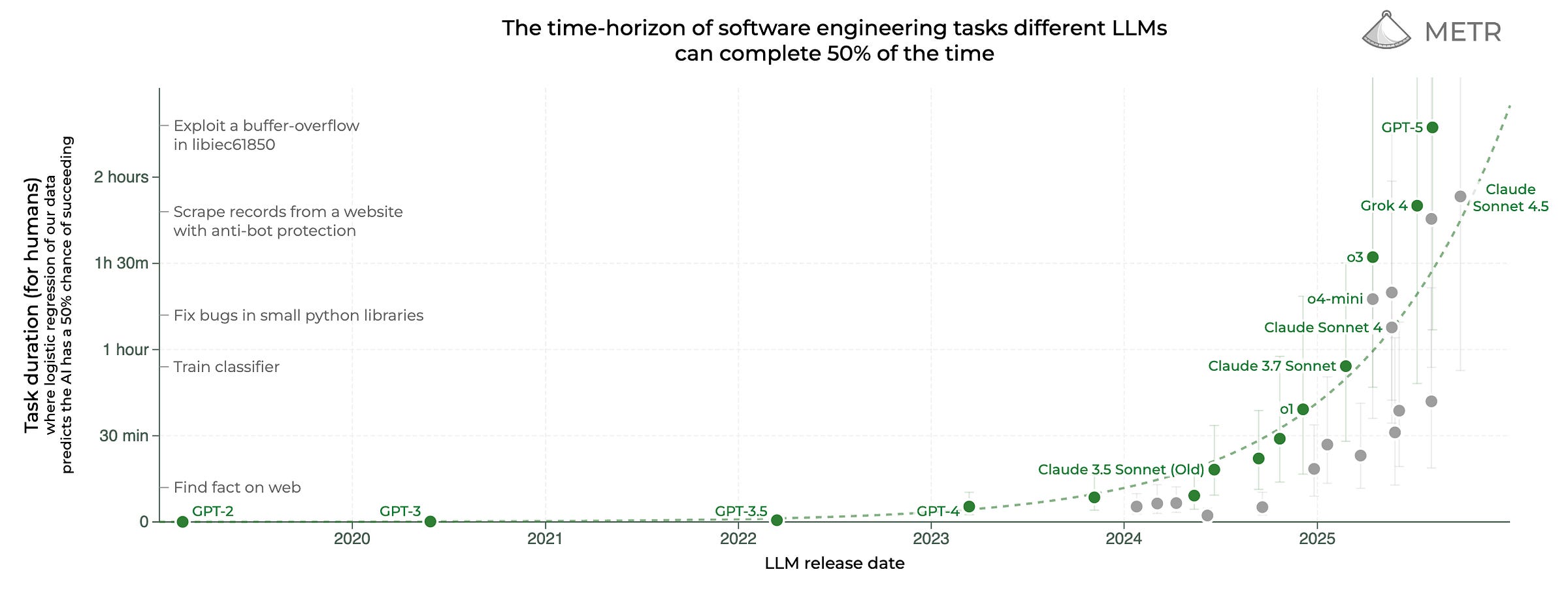

As weird as it sounds, an AI eventually automating the entire economy seems actually plausible, if current trends keep continuing and current lines keep going up. For one example, METR tracks how well AI is doing on software engineering tasks, an economically valuable activity. METR finds that models have dramatically increased in their capability, from only being able to do rudimentary toy problems a year ago to being able to stand-in for a non-trivial amount of work that actual software engineers actually do:

And Anthropic’s Claude Code is already generating over $500M by assisting in the development of software code. Trends for other tasks outside of software and math are not that fundamentally different, suggesting eventually AI will be able to assist with — and eventually automate — a bunch of other tasks as well.

So what will happen?

Unfortunately, forecasting is not the same as having a magic crystal ball and being a strong forecaster doesn’t give me magical insight into what the market will do. So honestly, I don’t know if AI is a bubble or not. Admittedly, OpenAI, NVIDIA, AMD, and other companies are engaging in a lot of weird financial arrangements. But there’s nothing wrong with these per se. I personally take the bubble possibility seriously.

But we need to think more clearly. And a lot of people want AI to fail and are just doing ideological pattern-matching to crypto/NFTs and declaring AI a pump-and-dump grift without evidence, and that’s not good analysis.

The key question is whether AI capabilities improve fast enough to generate economic returns before the debt comes due. OpenAI has demonstrated explosive revenue growth already and AI capabilities keep improving on clear trajectories. The underlying bet — that AI will be economically valuable — still looks fairly solid.

My assessment is that there’s roughly a 30% chance of a significant AI-driven market correction with at least a >20% drawdown in AI-heavy stocks, sometime within the next three years. This may or may not lead to a broader recession, that’s unfortunately beyond my ability to forecast.

The modal path (~55% probability) is OpenAI restructures deals and raises dilutive funding rounds, but capabilities keep improving and justify continued investment. Some commitments get renegotiated downward, or OpenAI IPOs at $300B instead of $500B. This reprices AI expectations but doesn’t crash the market.

So why are industry leaders calling AI a bubble while spending hundreds of billions on infrastructure? Because they’re not actually contradicting themselves. They’re acknowledging legitimate timing risk while betting the technology fundamentals are sound and that the upside is worth the risk.

Annualized revenue is a metric that is just the revenue of your most recent month multiplied by 12 to be a full year. It’s essentially a forward-looking view of how much money you’d make over the next year if all your months look like the month you just had.

Though of course comparing private companies to public companies is an unfair comparison. Private company valuations are based on illiquid preferred shares with liquidation preferences, while public market capitalizations reflect liquid common stock. The $500B likely overstates what OpenAI would be worth as a public company by 20-40%, which would place it lower in the rankings.

This includes an initial $11.9B cloud deal over 5 years with CoreWeave followed up with two separate expansions together adding another $10.5B to the tab

Revenue, revenue, revenue — this is all I keep hearing about. But valuation stems from (future, discounted) earnings, not revenue. If there was just OpenAI, then we could argue that losses will turn into profits due to falling training/inference costs and new revenue streams like ads or hardware.

But multiple deep-pocketed companies are pursuing products that have an almost commodity-like similarity. Cursor, for example, can switch from Claude to GPT to Gemini at will. This means pricing power is low and hence profits will be low. It’s perfectly possible that AI will be transformational and revenue will be in the hundreds of billions, yet valuations collapse because profits are competed away.

Great article overall, but I can't get past the disparity between how scrupulous your work generally is and the story about full automation driving your relative optimism, esp. insofar as it's justified by this (commonly misinterpreted) METR figure.

I imagine you've encountered the main criticisms, but just to throw in my two cents, not only are the tasks at issue highly parochial relative to the economy writ large, but 50% success is just nowhere near the reliability you'd need to justify any level of automation. And don't find the growth rate very convincing either given how categorically different the challenge of 99(.999...)% reliability is relative to 50.

There are of course a ton of further, independent reasons widespread automation is unlikely (such as political ones), but to imply it's plausible on the basis of this particular figure screams 'epistemic double standard' to me.