Weekend Links #1: Buying Greenland, model collapse

Also golden resolutions and what the best prediction market bettor has to say about the art of forecasting.

A good forecaster reads constantly. However, like the power laws this blog is named for, some readings matter far more than others. Each weekend, I'll share the standouts …along with some occasional fascinating rabbit holes. Some weekends will be light, others heavy (that's how power laws work), but each link will be worth your weekend morning coffee time.

AI

Synthetic data is more useful than you think and fears of ‘model collapse’ are overstated, at least for now, as reported by Lynette Bye for Transformer. I had personally been skeptical for awhile that synthetic data would be tremendously useful, but it seems like synthetic data is working fine now. This is in part because models are actually pretty good about reasoning about data quality and so can self-filter effectively, similar to how Constitutional AI / RLAIF works well. Moreover, you can get humans to do quality checks on the synthetic data.

Synthetic data also seems to be the basis for at least some of the improvements from o1 to o3, as models can synthetically generate different reasoning paths and then learn which reasoning paths get to the right answer (e.g., Gwern on LessWrong states: “Every problem that an o1 solves is now a training data point for an o3”).

Moreover, "model collapse" itself has thin empirical data, as it was studied on the tiny OPT-125M model from 2022 rather than any of the more powerful and modern models.

~

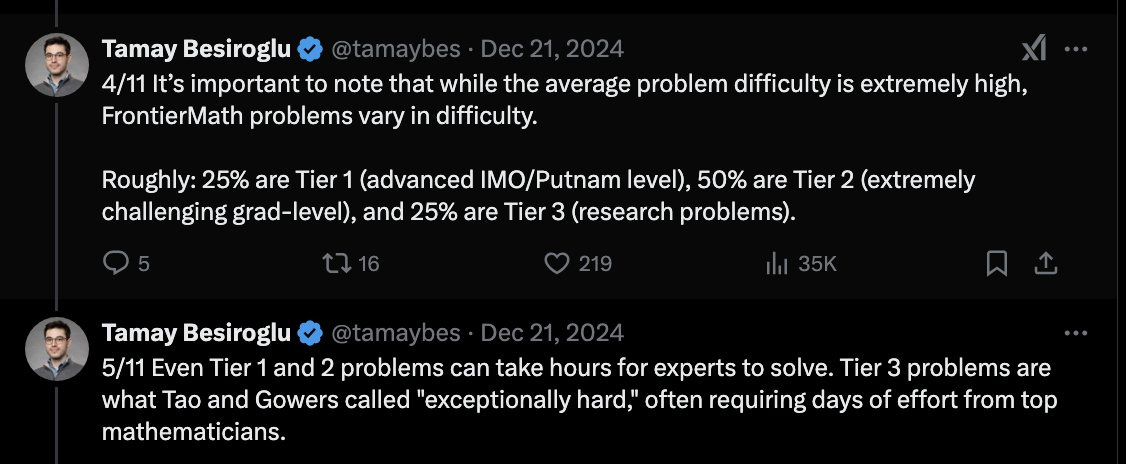

Meanwhile “o3-mini + tool use” has now reached a stunning 32% on the FrontierMath benchmark, including a 28% solve rate on the ‘Tier 3/3 challenging problems’ that famous mathematician Terence Tao called “extremely challenging”.

…Here’s one of the creators of FrontierMath explaining the different tiers and what they mean:

Forecasting

One of my favorite quotes about prediction markets, from Domer - the top prediction market bettor in the world with millions in net winnings:

I like to say [...] that making money in prediction markets is easy. The future is unpredictable, but not that unpredictable. You can easily find markets where you can make money. But the truly hard part of prediction markets is avoiding losing a lot of money on stupid stuff. Because as easy as it is to make money on prediction markets, it’s even easier to lose it.

…The rest of the interview is interesting too:

Domer prefers prediction markets to poker because there’s less variance and you can “out-research” others. He also prefers it to the stock market because there’s more direct and near-term results - you don’t have to wait years for a thesis to pay off.

He loses many bets but is overall net profitable because his wins are bigger than his losses.

He likens professional betting to a “rōnin-like” existence: mostly solitary, but occasional collaboration with fellow rōnin to avoid big mistakes. He also receives many “tips” via DMs from random people, has a small circle of trusted confidants, and talks through bets constantly with them for sanity checks.

Many of his bets start as small, gut-based trades. For large positions, he digs into more thorough research.

Domer loves the challenge of working on many different topics and is often drawn to brand-new markets where no one is an expert and everyone starts from near-zero knowledge. He takes this as a puzzle or race to see who can figure out the correct angle first.

The classic “top forecaster” versus “expert” plays out in favor of the forecaster — Domer believes deep subject-matter experts sometimes perform poorly in prediction markets because they tend to overweight their special knowledge and ignore other signals/factors.

His advice for new traders:

Start with $10 to $100 to experiment, don’t bet more than you can afford to lose because you will lose a lot.

Remember you’re never obligated to bet on any one thing. If you’re not sure you have an edge, do nothing or bet very small. If you do have a big edge, increase the size of the bet.

Bet in accordance with your assessed edge. If no edge: pass. If big edge: bet big. Many people overbet without a real edge and underbet when their edge does come along. But accurate self-assessment of edge is key.

Geopolitics

We’ve all heard that Trump wants to buy Greenland. But we forget that this has a historical parallel: the US also tried to buy Greenland right after World War II in 1946. However, Denmark’s rejection of the $100M sale (~$1.5B today) - seemingly motivated by national pride rather than strategic interests - was a consequential economic miscalculation.

Gwern writes in “Reasons of State: Why Didn't Denmark Sell Greenland?” that the decision not to sell cost Denmark billions. Greenland remains heavily dependent on Danish subsidies while generating minimal economic value. At the same time, despite not paying for it the US still got most of what they wanted from Greenland anyways, as Denmark ended up granting the US extensive military rights in Greenland through NATO agreements.

~

Have experts really gotten worse? Not really, says Matt Yglesias (paywalled article). Much of the current political mood in the US seems to be a backlash to expertise that hasn’t led to good results. And there are certainly are clear policy failures with the last US administration - such as COVID, inflation, and the border.

…But there were many policy failures in the past too. Look to World War I, the Treaty of Versailles, the Great Depression, the Vietnam War, managing expectations around China, and not anticipating the collapse of the Soviet Union or the re-rise of Russia after.

In fact, Yglesias argues that expert policy failure has been at worst constant, if not improving. The key difference though is that errors back then – especially smaller ones – don’t go viral like they do now. Thanks to the internet, we're simply more aware of mistakes and failures than ever before. Also, expert decision quality isn’t the only tension - there also is an issue of genuine values differences, especially around cosmopolitanism.

Lifestyle

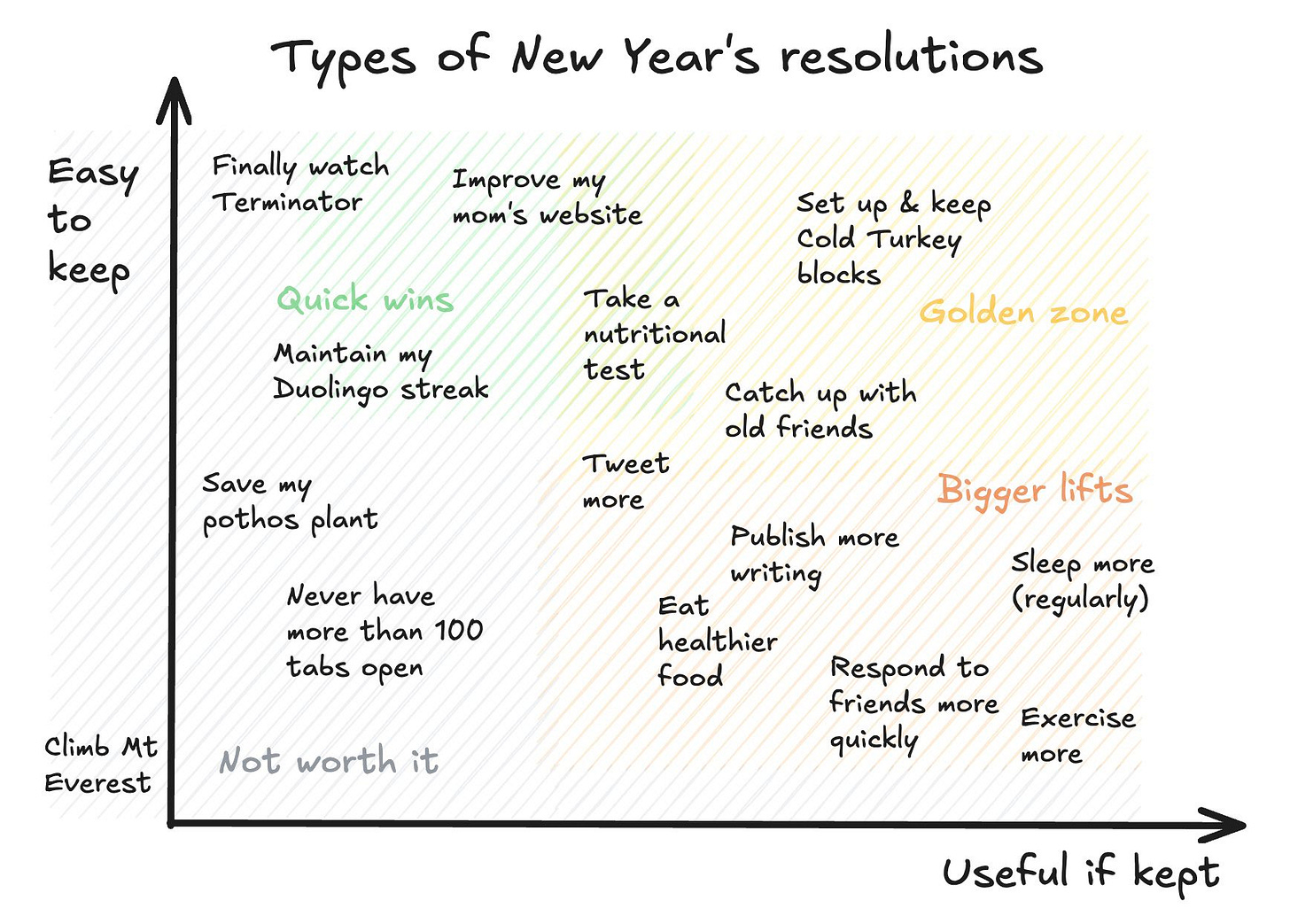

Lizka asks on Twitter: “Any favorite ideas for “golden” — easy and useful to keep — resolutions?”. Sadly not much feedback, despite such a useful concept.

~

The most valuable advice often comes not from industry giants but from those just slightly ahead of you in their journey on what you want to learn, Scott H Young argues in "Why the Smartest People Don't Always Give the Best Advice: The Importance of Local Wisdom". While conventional wisdom suggests you should most seek guidance from highly successful figures like Stephen King or Bill Gates, their advice can be less relevant to you due to two key factors: (1) the changing nature of what matters at different skill levels and (2) the changing nature of what is needed to succeed now instead of back when they succeeded. Moreover, once people become very successful, they tend to forget the real difficulties and struggles they faced early on, give advice that sounds good but isn't specific enough to be helpful, and lose touch with the current challenges and urgency that beginners face. Instead, seek ‘local wisdom’ from those just a few steps ahead of you to get more relevant, timely, and practical guidance.

~

What we call "lucky breaks" are often replicable opportunities we fail to systematize, Satvik Beri argues in "Systematic Lucky Breaks". While most people treat positive chance events as one-off occurrences, these fortunate moments actually can be reverse-engineered and deliberately reproduced. For instance, when a one-time game night during a community meetup happened to prove unexpectedly valuable for building relationships, Beri transformed it into a biweekly hosting routine that consistently deepened friendships.

Similarly, after discovering that reaching out to LinkedIn experts for advice on a challenging analytics architecture project saved months of work, he systematized this approach - regularly consulting subject matter experts at the start of new projects rather than waiting until desperation set in.

This approach to converting serendipity into system suggests that many of life's most valuable opportunities may not be as unrepeatable as we assume - they just require us to recognize and deliberately reconstruct the conditions that made them possible in the first place.

~

The hardest decisions we face may actually be the least consequential, Eliezer Yudkowsky argues in "Harder Choices Matter Less". While we often agonize over difficult choices, the very difficulty of the decision inherently suggests either (a) valuable information needs to be collected or (b) the options are nearly equivalent in expected value because if there were large differences in value the choice would be easier. Thus when faced with a truly difficult decision, the optimal response isn't further deliberation but either figuring out what more information is critical and gathering that, or making a quick choice to avoid over-analysis. This perspective suggests that our tendency to agonize over decisions may be misplaced, and our decision-making energy might be better spent on clearly differentiated choices or active information gathering.

~

The path to achievement lies not in mastering productivity systems, but in cultivating an obsession with finishing what you start. In "The Art of the Finish: How to Go From Busy to Accomplished", Cal Newport's research suggests that many highly accomplished people are actually quite disorganized. What sets them apart instead is their relentless drive to complete projects, whether through scheduled chunks or last-minute pushes. Newport's solution is "completion-centric planning" - a simple system centered on a single page of a few clearly defined projects across life domains, with daily focus on maximum progress toward completion rather than task management. By adopting this approach, followed by deliberate rest periods between project batches, individuals can move beyond mere busyness to genuine accomplishment, challenging the prevalent belief that better organization alone leads to success.

Whimsy

This is Andromeda’s actual size in the night sky (bigger/original version) if you somehow could see all of it, which of course you can’t. Real astronomers have fact checked this as true (see here and here).

~

A Google maps overlay that lets you discover the relevant wikipedia pages for the places near you (or where you have the map pointed at). Very cool!

~

Why choosing to run for Congress is basically the equivalent of one lightning $1M on fire, so maybe we could have a bit more sympathy for potential Congresspeople and raise their pay? Or maybe this explains a lot about who chooses to run for Congress?

This was great.

If tier 3 FrontierMaths problems are so much harder than the average problem, why is the solve rate so similar? A bit fishy at first glance...