The Munich Pivot: Understanding America's Shift from Europe to Asia

How resource constraints and realpolitik are forcing tough choices in US defense strategy

For decades, the Munich Security Conference has served as the premier international forum discussing geopolitical security, where American and European leaders typically reaffirm their commitment to European defense.

But late last week, US Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth delivered a different message: “stark strategic realities prevent the United States from being primarily focused on the security of Europe”. This marks a decisive shift in Republican foreign policy — according to Hegseth, America's resources are stretched too thin and China's rise demands America’s full attention.

Understanding Republican foreign policy

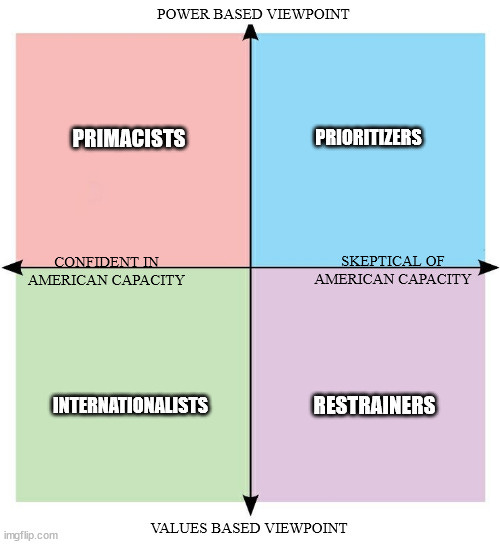

What to make of this sudden shift from Hegseth? This is best understood through a framework developed by foreign policy analyst Tanner Greer. His analysis breaks down current Republican thought along two key dimensions — (1) optimism versus pessimism about American military capabilities, and (2) power-based or values-based reasoning in deciding how to deploy those capabilities:

The Primacists, represented by figures like Former Secretary of State Mike Pompeo, believe America can maintain multiple large global defense commitments simultaneously, advocating for direct military intervention when necessary, including in Taiwan, and supporting strong Ukraine aid. Primacists view this defense as a matter of maintaining American military dominance and power projection.

The Internationalists, represented by Secretary of State Marco Rubio, emphasize coalition-building and see foreign policy through the lens of democracy versus authoritarianism. They also support both Taiwan and Ukraine, but for different reasons — seeing it not as power projection but about defending the ideals of democracy against a coordinated authoritarian threat that can't be separated into distinct regional challenges.

The Prioritizers argue for focusing resources primarily on the China threat while reducing other commitments, viewing aid to Ukraine as a distraction from the Asian theater. This is because the US simply does not have enough power and resources to be everywhere at once and thus must prioritize. This view was originally made prominent by Elbridge Colby, the Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense for Strategy and Force Development during Trump’s first term and Trump’s nominee for Defense Undersecretary for Policy in his second term. Vice President Vance also fits into this camp and it seems like Secretary of Defense Hegseth is in this camp as well.

Finally, the Restrainers, such as Rand Paul and Vivek Ramaswamy, advocate for broad retrenchment from foreign commitments, opposing both Taiwan intervention and Ukraine aid while emphasizing homeland defense. This view is similar to old-style isolationism suggesting that the US shouldn’t interfere in the affairs of other nations unless attacked.

Trump's competing foreign policy visions

While this framework illuminates the key divisions in current Republican foreign policy, assigning specific figures to these camps involves some uncertainty. Most importantly, assigning President Trump himself to this list is difficult, as Trump has deliberately avoided endorsing any detailed policy plans and keeps his options open. While Trump’s rhetoric often aligns with the Restrainer camp's skepticism of foreign interventions, his administration's actual policies frequently reflect a mix of approaches. For example, Rubio as Secretary of State suggests significant accommodation of the Internationalist view, while Vance as VP, Hegseth’s rhetoric, and the nomination of Colby indicates growing influence of the Prioritizer camp.

However, this fusion is also creating internal tensions. Colby's nomination for Undersecretary of Defense for Policy has generated notable Republican opposition, particularly regarding his views on Iran and broader Middle East policy — namely that the US should focus on this region much less in order to focus on China more effectively.

This is a broader challenge for Trump’s foreign policy. While there's strong consensus about the need to prioritize China, there's still very substantial disagreement about what that means for other commitments. Colby and other Prioritizers argue for significant retrenchment from the Middle East and Europe, while Internationalists like Rubio seek to maintain America's global role in these theaters while simultaneously strengthening Indo-Pacific capabilities. The ultimate direction of policy likely depends on which camp prevails in key bureaucratic battles, with Colby's confirmation process serving as an important indicator.

Prioritizers and the risk from China

In understanding the Prioritizer view one might reasonably question (a) why deterring China should be the top priority and (b) why the US cannot deter China while still simultaneously arming Ukraine and deterring Iran.

The Prioritizer answer is as follows:

China is US’s lone peer competitor. According to Prioritizers, it would take the entire US military and manufacturing might to properly counter China, leaving nothing left over to allocate to other theaters. This fact, combined with a deeply pessimistic view of America's political and bureaucratic capacity to handle multiple challenges simultaneously, suggest that the US should fully focus on China or risk giving up to China altogether.

Peer competition makes China a unique threat to the US. China alone has both the capability and potential motivation to fundamentally reshape the global balance of power away from US interests. Other nations can’t do that, absent nuclear war.

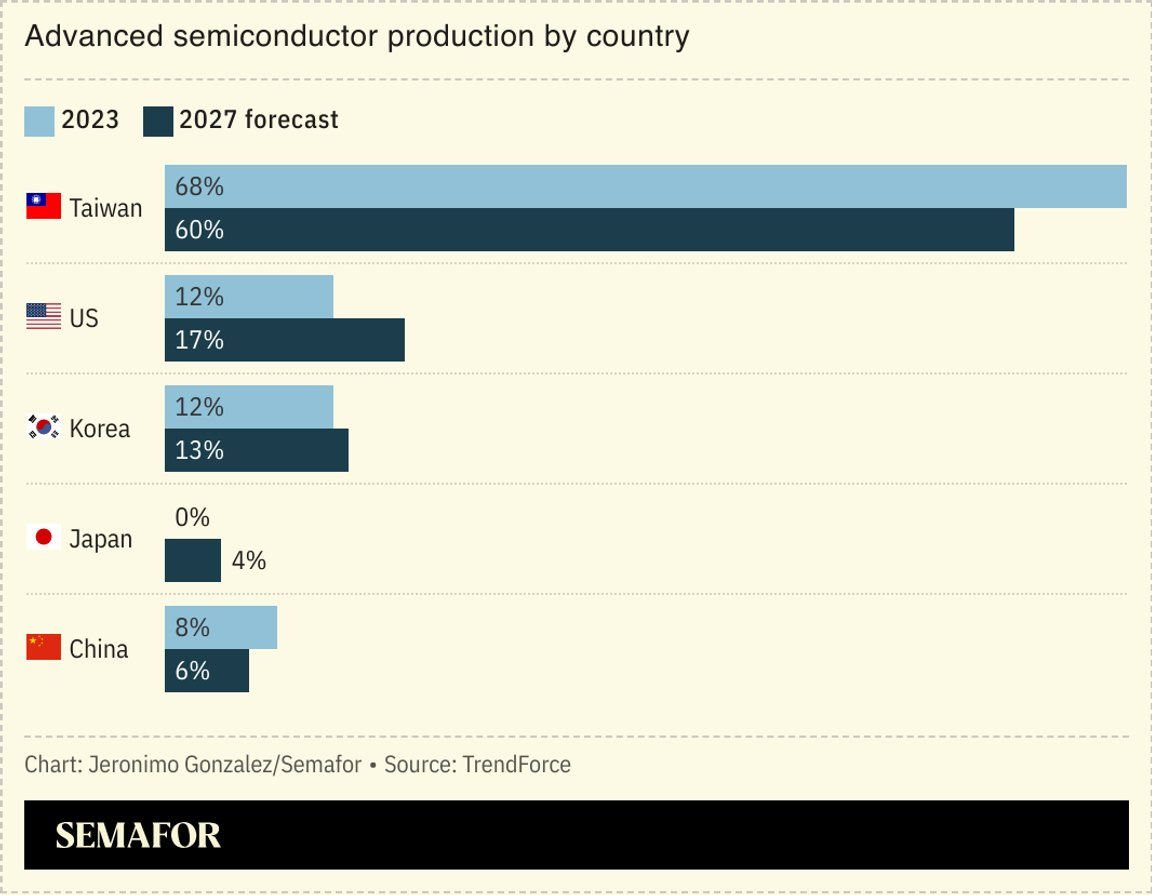

Advanced semiconductors are the key battleground for the future and defending Taiwan is key. Taiwan alone produces over 2/3rds of all advanced semiconductors. Taiwan's semiconductor industry directly impacts US technological and military capabilities. A Chinese takeover of Taiwan would give China leverage over nearly all advanced technology production.

The Taiwan Strait specifically — and the South China sea broadly — serve as a crucial maritime chokepoint. Nearly $3 trillion in annual trade flows through the Taiwan Strait. Chinese control of the Strait would give them direct control over a lot of shipping, as well as allow them to extend their force across the entire South China Sea. This would give China significant additional leverage over Japan, South Korea, and Southeast Asia.

A failure to defend Taiwan could cause Japan and South Korea to come under threat and/or reconsider their US alignment. This could lead to nuclear proliferation in Asia as countries seek independent deterrence.

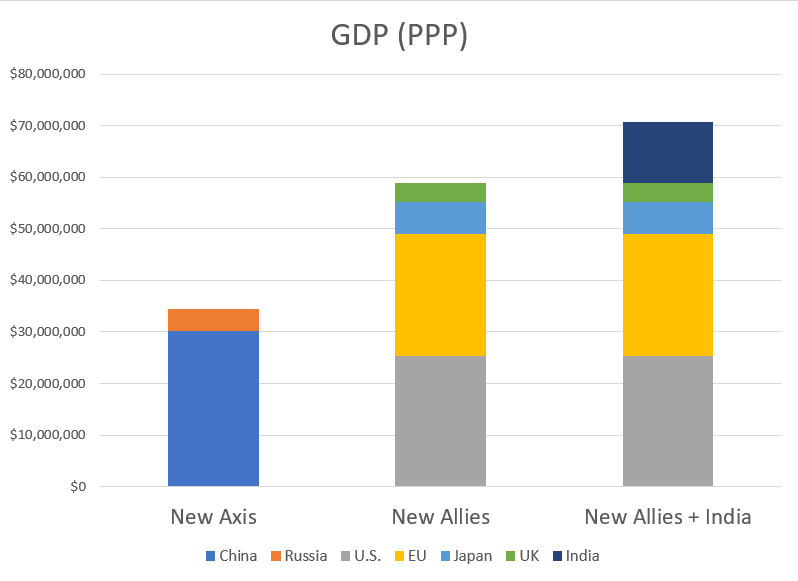

In “Sizing up the New Axis”, economist Noah Smith identifies China's massive manufacturing base, advanced technology, and enormous population as uniquely threatening. According to Smith, China poses more of a military challenge to the US than either Nazi Germany or the Soviet Union did.

The data is striking — China’s GDP is larger than the US when adjusting for Purchasing Power Parity (PPP) and China’s manufacturing output is dominant:

More worryingly, China’s manufacturing has particular strengths in critical dual-use areas like shipbuilding, electronics, and advanced materials that far exceed US capacity. This allows China to rapidly surge military production, as demonstrated by its recent naval buildup, while maintaining control over key civilian and military supply chains.

This manufacturing advantage of China over the US should not be underestimated. In "People are realizing that the Arsenal of Democracy is gone", Noah Smith further paints a stark picture of American unpreparedness. US manufacturing of critical military supplies have atrophied — monthly artillery shell production has fallen from 867,000 in the 1990s to just 28,000 today, while American shipbuilding capacity is estimated at only 0.5% of China's. Meanwhile, American businesses remain deeply dependent on Chinese supply chains, with 18% of U.S. imports still coming from China despite recent diversification efforts.

Additionally, China has achieved parity or superiority in several crucial technological domains, including hypersonic weapons and quantum communications. Their systematic integration of civilian and military research through Military-Civil Fusion creates advantages that America's segmented research ecosystem struggles to match. The US maintains superiority in AI technology, but this advantage is not guaranteed to last.

Lastly, geographic advantages further compound these Chinese advantages. China enjoys local superiority in the Western Pacific, with extensive land-based anti-access/area denial capabilities and short internal lines of communication.

This necessitates a fundamental reorganization of Western economies to rebuild domestic manufacturing capabilities, secure vulnerable supply chains, and ultimately prepare for a potential war. These resource constraints make it increasingly difficult to maintain credible deterrence across multiple theaters.

The Future of European Security

Given these fundamental constraints on American power and the unique challenges posed by China, a key question emerges: how should Europe respond to reduced American commitment? The answer lies in examining Europe's own defensive capabilities and the potential for increased NATO burden-sharing.

It’s important to understand that the US pivot to Asia need not leave Europe vulnerable. Rather, it provides an opportunity — and perhaps necessary pressure — for Europe to finally take responsibility for its own defense. The primary obstacles are not material capabilities but European political will and coordination.

Europe possesses far greater latent hard power than is commonly recognized — European countries dramatically outmatch Russia in population, manufacturing output, and economic power. The same graphs above that showed the strength of China relative to the US also show that the EU + UK are much larger than Russia in population, GDP, and manufacturing output.

Additionally, Europe has technological superiority against Russia across many relevant battlefield technologies such as precision-guided munitions, air defense systems, electronic warfare capabilities, drone technology and counter-drone systems, aerospace manufacturing, and advanced materials. Furthermore, Europe maintains its own independent nuclear deterrent through France and the UK.

This suggests Europe has the fundamental capacity to defend itself from Russian aggression without needing to rely on American support. The scale of the EU-Russia economic disparity means that a united Europe could outproduce Russia in any extended conflict.

Much ado about NATO defense spending

The next step is for Europe (and Taiwan) to increase their own defense spending and stop relying on the US. Following the end of the Cold War, European NATO members dramatically reduced military expenditures from an average of 3.1% of GDP in 1985 to around 1.4% by 2015. This reduction was likely shortsighted, stemming from the perceived disappearance of threats, expanding social welfare commitments, and implicit overreliance on US security guarantees.

The 2014 Russian invasion of Crimea and pressure from Trump during his first term marked a shift in NATO, and this shift ramped up a lot following Russia’s full invasion of Ukraine:

However, this welcomed increase to 2% is still likely not sufficient. The US still has the third-highest spending on military as a percentage of GDP (at 3.4%) among NATO members, with only Poland and Estonia spending more:

Given the US’s larger GDP, the US spends more on defense than the rest of NATO combined.

Following this situation, the Trump administration has moved beyond previous demands for 2% to explicitly setting 5% targets. 5% may admittedly be too difficult given it would require politically unappealing cuts to social programs, but 3% is a realistic target that Europe should hit across the board.

These spending trends illustrate a key tension: while NATO members have shown willingness to increase defense spending under pressure, they haven't yet reached levels that would enable true strategic autonomy from the US.

Looking Forward

Of course, a pivot to Asia isn't new. In 2011, President Obama announced his own “pivot to Asia”, reflecting growing concerns about China's rise and recognizing Asia as the key theater for 21st century geopolitics. However, this attempted reorientation was repeatedly derailed by crises in other regions — from ISIS's emergence to Russia's invasion of Crimea — highlighting the persistent challenge of balancing global commitments.

Trump’s first term saw again an attempt to pivot to Asia, with increased trade wars, use of export controls, significant increased defense spending in the Indo-Pacific, engagement with Japan and Australia, and increased arms sales to Taiwan. However, Trump was not solely focused on China, continuing operations against ISIS, fighting Iran culminating in the strike that killed Qasem Soleimani, and remaining involved in entanglements with Yemen and Saudi Arabia.

This pivot continued into the Biden administration with the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework and strengthened regional alliances through initiatives like AUKUS. However, Russia's invasion of Ukraine and Hamas’s attack on Israel made this pivot difficult to sustain and Biden took an Internationalist stance. Nonetheless, Biden emphasized that China remains “the only competitor potentially capable of combining its economic, diplomatic, military, and technological power to mount a sustained challenge to a stable and open international system.”

However, Trump’s second term might finally be different. This is due to the combination of three factors: a clear-eyed Republican recognition of resource constraints, Europe's demonstrated capability to defend itself, and an even deeper American consensus about the unique challenge China poses. While previous pivots faltered because they tried to maintain America's global role while adding Asian commitments, the Prioritizer camp offers a more realistic path: acknowledging that effective competition with China requires difficult choices about America's global commitments.

As history shows, such a pivot is far from guaranteed — America's pivot to Asia remains a consistent intention with inconsistent execution. Internal Republican divisions, particularly visible in the debate over Colby's nomination, may further complicate implementation. And as we saw with Obama, Biden, and even Trump’s first term, new international challenges might emerge that tempt American resources.

Thus whether Hegseth’s strategic clarity can finally overcome the perennial challenge of global crisis management remains to be seen. But if it can be pulled off, it may be for the best. This proposed realignment, while potentially disruptive to Europe in the short term, may ultimately prove necessary both for ensuring Europe’s long-term strength and ensuring effective long-term competition with China. Success depends on two critical factors: Europe's ability to fill the resulting security gap before it becomes a vulnerability, and the Trump administration's capacity to maintain a coherent strategy despite internal ideological tensions. Hopefully both the Trump administration and Europe can meet this important moment.