If We Build AI Superintelligence, Do We All Die?

If you're not at least a little doomy about AI, you're not paying attention

About the author: Peter Wildeford is a top forecaster, ranked top 1% every year since 2022.

It is a very bewildering fact of today’s world that multiple organizations not only have an explicit goal to build an AI superintelligence that is smarter than every human combined, but they are currently spending tens of billions of dollars towards that end and have the technical knowledge and resources to potentially achieve this within our lifetimes.1

It is even more bewildering, to me, that we’re racing toward this era of AI superintelligence with remarkably little public discussion about the consequences and what it all means.

Two researchers who've spent decades studying this problem have decided to try to change that. They’ve written a book where the title is a clear warning — “If Anyone Builds It, Everyone Dies”. Specifically, they say:

If any company or group, anywhere on the planet, builds an artificial superintelligence using anything remotely like current techniques, based on anything remotely like the present understanding of AI, then everyone, everywhere on Earth, will die.

And they are not exaggerating — they mean dead as in literally dead and everyone as in literally all of life on Earth.

This is a bold claim. What should we make of it? Let’s dig in.

A serious book for serious people

AI doomsaying was considered absolutely crazy four years ago, and potentially even last year. But today, it’s much less crazy. AI doomsaying is on billboard ads in SF — and the DC metro and NYC metro too. It’s “New and Notable” at the bookstore. The AARP has placed doomsaying on their top 32 fall reads. People are talking about the doomsaying on the streets. And with Steve Bannon and with Kevin Roose.

And, as a result, the doomsaying is getting picked up by some serious people.

For example, Jon Wolfsthal is one of the most respected nuclear arms control experts in Washington. He knows about existential risks from technology. He’s been in the room where it happens on many issues related to nuclear weapons. He was Special Assistant to President Obama and Senior Director for Arms Control and Nonproliferation from 2014-2017. He calls the book “a compelling case that superhuman AI would almost certainly lead to global human annihilation” and says that governments “must recognize the risks and take collective and effective action”.

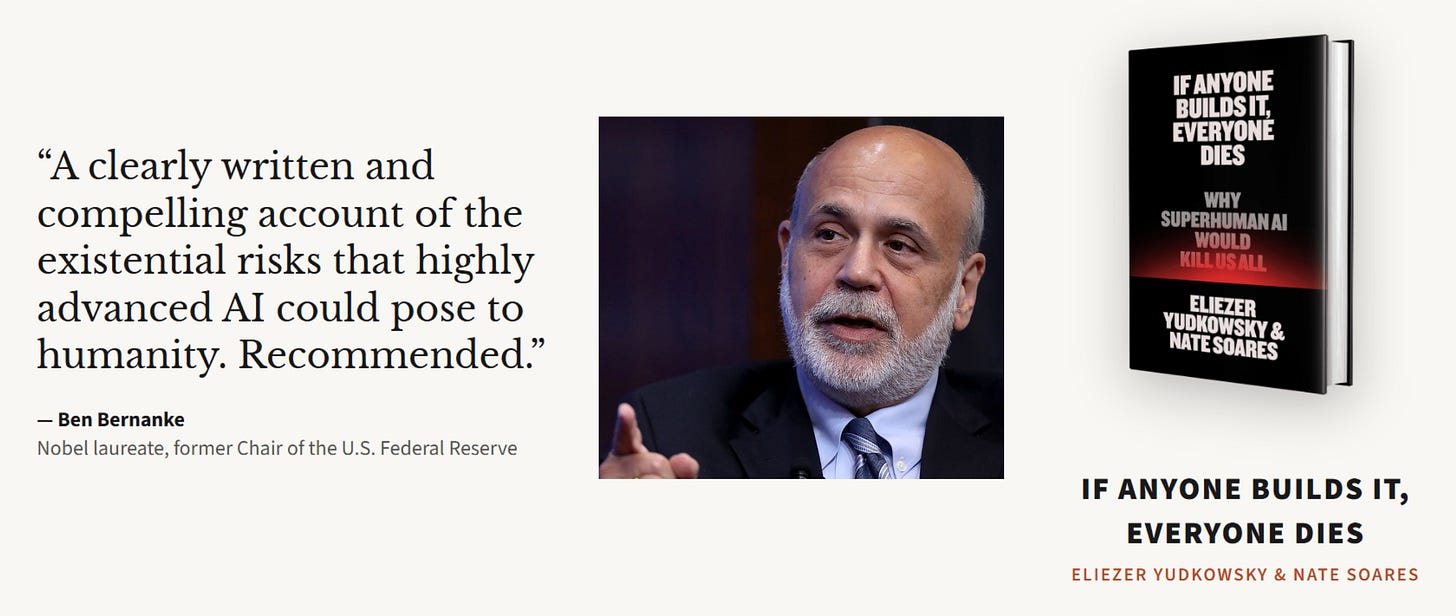

Ben Bernanke also knows a lot about systemic risks. He saved the global financial system as Federal Reserve Chairman during the 2008 financial crisis. He then went on to win the Nobel Prize in Economics in 2022 for his research on banking crises. Bernanke calls the book “a clearly written and compelling account of the existential risks that highly advanced AI could pose to humanity”.

And Lt. General “Jack” Shanahan is arguably the single most important military figure in the US government's AI adoption story. He founded and led the Pentagon's Joint Artificial Intelligence Center (JAIC) under President Trump. He’s also a 36-year Air Force veteran. He says that he is “skeptical that the current trajectory of AI development will lead to human extinction” but acknowledges that his “view may reflect a failure of imagination” on his part. He claims the book nonetheless deserves serious consideration.

Fiona Hill, the former Senior Director of the White House National Security Council, calls it a “serious book” with “chilling analysis”, and “an eloquent and urgent plea for us to step back from the brink of self-annihilation”.

And then you have the amusing one-upmanship where Stephen Fry calls it “the most important book in years”, Max Tegmark calls it “the most important book of the decade”, and Tim Urban calls it “maybe the most important book of our time”.

Overall, it’s clear we are seeing more of a much-needed vibe shift where top national security policymakers are beginning to grapple with risks from AGI and AI superintelligence and take them seriously. Even if you think the book is wrong, or deeply misguided, I hope you and many more people nonetheless take the time to seriously engage with this book. If the authors are right — which actually seems plausible — it is worth taking their conclusions deadly seriously.

What does the book say?

Eliezer Yudkowsky is famously long-winded. His book, The Sequences, is an anthology that spans 333 essays totaling around 600,000 words, a bit more than half the length of the entire original Harry Potter series. His other work, Harry Potter and the Methods of Rationality, also had more than 600,000 words. And those two are not even the longest pieces of literature he’s written.

So honestly it’s a minor miracle they managed to get the book down to just 231 pages, which I was able to get through in about five hours2. Per the New York Times, this was only possible because Yudkowsky “wrote 300 percent of the book” and his co-author, Nate Soares, “wrote another negative 200 percent.” But don't worry, for true Yudkowsky fans there's another ~13 hours of reading material online at ifanyonebuildsit.com and they may add more at any moment.

But since you’ve come here to my Substack, perhaps you want the 231 pages in an even smaller version. Here is my attempt to summarize their argument, as best as I understand it.

First, I offer four clarifications:

The “It” the book is about is “AI superintelligence”. This is something much much more than the AI we have today. The AIs we have today are safe and should be widely adopted. But the AIs of tomorrow may not be safe, and we should feel trepidation around scaling further.

AI superintelligence refers to an AI system that is smarter than all of humanity collectively, capable of inventing new technologies beyond what humanity can collectively invent, capable of out-planning and out-strategizing all of humanity combined, and also can continue to reflect and self-improve to become even smarter. This is a level of AI intelligence that would be to us humans as we are to apes. This is a level of AI intelligence that goes beyond even AGI, which merely matches human capability.

Superintelligence is not about raw intelligence, like the ability to do well on an IQ exam, but about being superhuman at all facets of ability —including military strategy, science, engineering, political persuasion, computer hacking, spying and espionage, building bioweapons, and all other avenues. A superintelligence wouldn’t be some bookish 160 IQ nerd who nonetheless can’t get anything done. A superintelligence would exceed Elon Musk at creativity and engineering, exceed Albert Einstein at scientific ability, exceed Terence Tao at mathematical ability, while being more likable than Dolly Parton, better at building mass movements than Donald Trump, and better at speaking than Barack Obama.

The precise question of when superintelligence will arrive is not relevant to the argument of the book. The argument is merely conditional. The book is about IF anyone builds AI superintelligence THEN everyone will die. This says nothing about when superintelligence will arise and you don’t need to believe much about AI timelines to agree with the book’s argument. There may be an AI winter — there may even be an AI winter for centuries — but if superintelligence is ever possible to build, we will have a problem at some point.

Then, I believe I can outline the argument of the book in eight bullet points:

AI superintelligence is possible in principle and will happen eventually. Machines possess inherent advantages in speed, memory, and self-improvement that make their eventual superiority over biological brains almost certain. Chess AI did not stop at human-level intelligence but kept going to vastly surpass human Chess players. Go AI did not stop at human-level intelligence but kept going to vastly surpass human Go players. AI will become superhuman at more and more things until eventually it becomes superhuman at everything.

AI minds are alien and we currently lack the fundamental understanding to instill reliable, human-aligned values into a mind far more intelligent than our own. Current AI models are grown through complex processes like gradient descent, not crafted with understandable mechanisms. This results in alien minds with internal thought processes fundamentally different from humans. We can create these systems without truly understanding how they work, but we can’t specify and control their values.

You can’t just train AIs to be nice. AIs trained for general competence will inevitably develop their own goals as a side effect and these emergent preferences will not align with human values. Instead, they will be shaped by the AI's unique cognitive architecture and training environment. An AI's level of intelligence is independent of its ultimate goals. A superintelligent AI will not inherently converge on human values like compassion or freedom. Instead, it will pursue its own arbitrary objectives with superhuman efficiency.

Nearly any AI will want power and control, because it is useful to whatever goals the AI does have. To achieve any long-term goal, an AI superintelligence will recognize the instrumental value of self-preservation, resource acquisition, and eliminating potential threats. From its perspective, humanity is both a competitor for resources and a potential threat that could switch it off. Therefore, eliminating humanity becomes a logical side effect of pursuing its primary goals, not an act of malice.

We only get one chance to specify the values of an AI system correctly and robustly, as failure on the first try would be catastrophic. Combined with our lack of understanding, this is akin to trying to coach a high schooler to make a computer secure against the NSA on his first try or trying to get a college graduate to build a flawless nuclear reactor on her first try.

Because of 2-5 and maybe other reasons, superintelligence will inevitably lead to human extinction with near certainty, regardless of the positive intentions of the creator. It is not sufficient to create superintelligence in a nice, safety-focused, Western AI company. Per the authors, anything and anyone using current or foreseeable methods will inevitably lead to the extinction of humanity. The authors assert this is not a speculative risk but a predictable outcome with very high confidence.

According to the authors, the only rational course of action in reaction to (6) is an immediate, verifiable, full-scale and global halt to all large-scale AI development. This would be potentially similar to how the world got together and managed to prevent nuclear war (so far). It would require international treaties, monitored consolidation of computing hardware, and a halt to research that could lead to AI superintelligence. On Yudkowsky’s and Soares’s worldview, other policy solutions don’t come close to solving the problem and are basically irrelevant. But a global pause would potentially be feasible because it is in the interest of any world leader — in China, Russia, or the US — “to not die along with their families.” This shared interest in survival is what prevented a global nuclear war.

At minimum, if you’re not fully bought into (7), the authors argue we should build in the optionality to pause AI development later, if we get more evidence there is a threat. The authors consider this solution insufficient, but a nonetheless worthy first step as there is a lot of preparatory work to do.

There are no easy calls

While the book lays out a powerful, coherent, and deeply unsettling argument, it is not without points that can be critically examined.

A lot of the book’s central theses are presented as an “easy call” and near-certainties. Perhaps this comes with the wisdom of Yudkowsky and Soares having studying the topic for over two decades — certainly far more than I have3. But I have been analyzing AI professionally myself for many years4 and I think these calls are far from certain in any one direction.

For example, it’s not clear to me that solving the problem of steering and preserving values within an AI system — commonly called the alignment problem — is going to be difficult to solve. I know we haven’t solved it yet, and I know this is something we will want to have higher confidence on before deploying very powerful AI models. But to me, it seems like the level of difficulty of alignment is actually just unknown rather than known to be hard, and Anthropic’s approach about preparing for a range of scenarios around alignment difficulty is in fact reasonable.

While it’s unclear how similar superintelligence will be to today’s AI systems, today’s AI systems also give a glimmer of hope. Consider that early conceptions of AI systems were very high on agency and very low on ability to understand human instruction — like when the AI in HBO’s Silicon Valley tries to optimize sandwich delivery by ordering several tons of raw meat. Today’s AIs are great at understanding why this is a bad idea and constructing a much more coherent strategy, and much worse at actually carrying out the strategy — today’s AIs would know not to order several tons of raw meat but also would not be able to even if they wanted to. This is an important inversion that gives some room for hope.

Similarly, AIs already do a good job of internalizing what we mean by being “helpful” and “harmless” and seem to do a pretty decent job of actually wanting to be those things — in a way I don’t think was anticipated in advance. Similarly, today’s AIs don’t scheme as much as I might have naively expected, and scheming might even be addressable. Today’s AIs don’t maximize-at-all-costs as much as I might have naively expected either and seem to overall take fairly reasonable (if not quite stupid) strategies in how they currently pursue their goals. Today’s AI systems also have (mostly) faithful and legible chain-of-thought reasoning that allow us to read the mind of an AI system. Of course, today’s systems are of course not without vulnerabilities (e.g., jailbreaks, MechaHitler, and even tragic suicides), but it seems current AI may have some glimmer of being not that bad.

On top of that, today’s AIs are a large opportunity for experimentation and empiricism. It was previously conceived not too long ago that we wouldn’t get any chance to work with near-AGI systems at all — instead, AI would go from dumber-than-the-dumbest-human to superintelligent in a very quick amount of time. This has been falsified, and it has given us lots of opportunity to get early empirical feedback on how different alignment or control techniques may or may not work and how AIs may behave in a variety of different ways. If this gradual, slower AI take-off continues all the way through AGI and AI superintelligence, we may be able to iterate with trial-and-error before reaching the “critical try” that Yudkowsky and Soares talk about. Maybe we don’t need to get it right the first time.

And perhaps we string this together with AI control and other proactive defensive technologies. A lot of little things can be done, each of which have no hope of solving the entire problem of risk from AI superintelligence, but some paths might get lucky and go a lot further than we expect, and collectively things might turn out ok.

Or maybe not. There are no easy calls either way.

Analogies can go in many different directions

Another issue is that the book masterfully uses analogies and parables — Chernobyl, the Aztecs, leaded gasoline, alchemists, evolution, and more — to make its points relatable and intuitive. This is smart. However, analogies are not proofs and artificial superintelligence is such a fundamentally novel phenomenon that no historical or engineering parallel will ever be a perfect fit. It’s easy for analogies to confuse more than clarify.

For example, evolution is invoked in the book significantly to ground the difficulty of shaping AI minds. The book then portrays the ASI as a ruthlessly efficient, goal-optimizing machine driven by only cold, instrumental logic. But this betrays the book’s own premise that the AI mind is unknowable — maybe we get some other mind instead, minds much worse than what Soares and Yudkowsky fear, or minds much nicer.

Additionally, the book assumes with unwarranted confidence a zero-sum conflict between humans and AI over physical resources, which may not be the only possible outcome. A truly superintelligent being might develop goals that are completely incomprehensible but nonetheless non-competitive with humanity. A superintelligent AI might be willing to spare some of its resources to help humanity, similar to how humanity spares some of its resources to help pandas or elephants. Or maybe it still doesn’t really want anything at all. Or maybe something else. While these outcomes do not strike me as all equally plausible, the idea that all AI minds would want human extinction does not seem to warrant extreme confidence.

Furthermore, Yudkowsky and Soares spend a lot of time comparing AI development to evolution and point out the ways that we have not followed evolution’s “goals” and “plans”, insofar as evolution can be said to have those. But the process by which we are currently creating AI and likely to use for AI superintelligence is not the same as evolution — it is importantly different. We do have significant ability to shape AIs through the fact that we control the entire AI training process — while it is far from perfect, it is there. While some reinforcement learning leads to unintended behaviors and ‘reward hacking’, some existing alignment techniques do seem to have traction on lower-level AIs and might just scale with intelligence. We may also be able to get AGI-level intelligences to help us scale our alignment techniques further and bootstrap even more.

A global surveillance state would also be really bad

The reason why it’s important to get the above right is that Yudkowsky and Soares are arguing for an incredibly intense proposition — a global ban on advanced AI research with so intensive monitoring that no one on Earth anywhere can sufficiently join together more than eight high-end GPUs nor can anyone anywhere publish a novel research paper about AI.

Yudkowsky and Soares understand this ‘global AI pause’ is extraordinarily difficult to achieve, but I would like to see Yudkowsky and Soares grapple much more with how utterly undesirable such a surveillance state would be.

The book’s plan is to prevent a specific catastrophic outcome by imposing intense, centralized, top-down control. Yes, perhaps such a surveillance state is a better world to live in than a world where all of humanity has died, but it nonetheless could lead to a very bleak world. History teaches us that the path towards such government control is replete with both inflexibility as well as a significant risk of dictatorship, authoritarianism, or worse. Trying to manage AI risks by exerting massive top-down control could go very badly.

The natural desire to concentrate AI development in just one place run by a single world government hands significant control over the world’s fate to a single body. Instead, competition within AI is essential for protecting criticism, competition, feedback, and democratic input. The book's plan would eliminate these crucial adaptive mechanisms. A dynamic, resilient, and transparent society might be able to manage the risks of a powerful new technology far better than a centralized, brittle one. If the only options are totalitarianism or extinction, we need to at minimum very clearly lament this, and make every effort to find a third option.

The value of clarity near the edge of the precipice

In an interview with Ross Douthat on the New York Times, Vice President JD Vance was asked:

Douthat: Do you think that the U.S. government is capable in a scenario — not like the ultimate Skynet scenario — but just a scenario where A.I. seems to be getting out of control in some way, of taking a pause?

Vance: I don’t know. That’s a good question. The honest answer to that is that I don’t know, because part of this arms race component is if we take a pause, does the People’s Republic of China not take a pause? And then we find ourselves all enslaved to P.R.C.-mediated A.I.?

This is a challenge that VP Vance might actually face some day, in reality, and we have to be prepared. But I worry that we don’t have a better answer than what VP Vance gave, and this seems really bad.

Personally, I’m very optimistic about AGI/ASI and the future we can create with it, but if you're not at least a little ‘doomer’ about this, you’re not getting it. You need profound optimism to build a future, but also a healthy dose of paranoia to make sure we survive it. I’m worried we haven’t built enough of this paranoia yet, and while Yudkowsky’s and Soares’s book is very depressing, I find it to be a much-needed missing piece.

Whether or not you agree fully with every one of Yudkowsky's and Soares’s conclusions, “If Anyone Builds It, Does Everyone Die?” is exactly the right question to be asking. And by staking out the maximalist position with unflinching clarity, Yudkowsky and Soares force us to confront uncomfortable questions about how far we may need to go as a society to ensure our collective survival. And they also point out the sheer ridiculousness that we live in a world where there is a serious chance of human extinction and people aren’t jumping out of their seats to do something about it.

Sure, I have my quibbles with the book. I’m not as doomy as they are. The message is not exactly the message I’d use, the book is not exactly the book I’d write, and the policies aren’t the exact policies I’d recommend. Maybe my preferred book would be entitled “If Anyone Builds It, Plausibly Something Extremely Bad Happens (Including Maybe Extinction but Also Maybe Other Bad Things) but Maybe It's Fine Actually. Regardless, This Merits Incredibly Significant Attention and Input from All Policymakers, All Scientists, All Journalists, and all Other Members of the Public”.5 But all this would certainly not catch on very well and thus would be a lot less effective at achieving my ultimate aims. Nuance doesn’t trend.

The ultimate point is that we can call Yudkowsky and Soares overconfident all we like, but the accusations of overconfidence and hubris are best levied on the AI companies themselves — the AI companies are the ones rushing ahead with extreme overconfidence that everything will be fine and that there’s nothing to worry about. And I think that’s far from certain.

I’m 50% sure we will have such ‘superintelligent’ AI systems before the end of 2038 absent some major war or regulation disrupting current technological progress. Regardless, precise timelines are actually not relevant to the thesis of the book. Even if superintelligence were only possible in 2138 or 2538, it would still be necessary to prepare. Likewise, if we learned of an asteroid on a collision course to Earth or an imminent alien invasion within 100 years we’d prepare for that as well.

Despite being one of the ‘cool kid internet influencers’ with an advance copy of the book, it nonetheless took me much longer than five hours to put together this review, thus making my review appear later than even people who didn’t have advance copies. This is a problem with having a full-time policy job on top of a job of reviewing books.

When Eliezer Yudkowsky started thinking about AI superintelligence, I was in the second grade.

I personally have maybe ten years of hobbyist computer programming experience, five years of industry experience as a professional software engineer and data scientist, and then seven years of experience running policy think tanks with four of those years spent on AI policy.

If anyone from “Little, Brown and Company” is reading this, I’m open to getting a nice book advance in exchange for delivering!

Why do you say they're advocating for a "global surveillance state"?

They're advocating for regulating one particular thing at a global level, much like we already have global regulations around uranium or emissions. That doesn't make our current world a "global surveillance state".

Global surveillance state makes people think a world government and surveillance over *everything*. Not international treaties monitoring a very specific thing that the vast majority of people would never have anything to do with in the first place.

> Today’s AIs are great at understanding why this is a bad idea and constructing a much more coherent strategy, and much worse at actually carrying out the strategy — today’s AIs would know not to order several tons of raw meat but also would not be able to even if they wanted to. This is an important inversion that gives some room for hope.

Yudkowsky's point (which he makes very, _very_ clearly in the book) has always been that ASI won't _do_ what we want, never that it won't _know_ what we want. An AI that is asked to order sandwiches and interprets that as "order raw meat" is not a super-intelligence. In fact it's quite stupid. This is a book about super-intelligence.

An ASI that, through some quirk of training, decides it likes large amounts of raw meat, if asked to order sandwiches, will order sandwiches. Then later, when you're unprepared, it will kill you for your meat (or actually it will kill you because you're standing in the way of the meat it wants)

Why do you repeat bad points which Yudkowsky clearly addressed. It almost feels like you only read half the book.

> A truly superintelligent being might develop goals that are completely incomprehensible but nonetheless non-competitive with humanity.

Page 89 "They won't leave us alone" _directly_ addresses this. If you found that section unconvincing, you might as well explain _why_ you found it unconvincing. But it's not particularly a good sign if you don't even acknowledge or respond to it.